Your procurement lead presents two quotes for 1,200 leather notebooks. Supplier A offers $18 per unit with a 500-unit MOQ. Supplier B offers $15 per unit with a 1,200-unit MOQ. The math appears straightforward: accepting Supplier B's MOQ saves $3,600 on the purchase order. Your finance team approves the decision based on cost per unit, and the order is placed.

Six months later, your competitor launches a nearly identical notebook line at a lower price point. Your sales team urgently requests budget for a counter-marketing campaign and a limited-time promotional bundle. The finance director reviews available cash and discovers $14,500 is tied up in 680 unsold notebooks sitting in your warehouse—inventory purchased specifically to meet that MOQ requirement six months ago. The marketing campaign is delayed by eight weeks while the company waits for inventory to convert to cash. By the time your promotion launches, your competitor has secured distribution agreements with three major corporate clients you had been targeting. The $3,600 you saved on unit cost ultimately cost you $47,000 in lost first-year revenue from those accounts, plus an additional 14 months of relationship-building to regain competitive position.

This scenario repeats across procurement teams with unsettling frequency, yet the underlying miscalculation rarely appears in post-mortems or budget reviews. The error isn't in the arithmetic—Supplier B genuinely offered a lower per-unit price. The misjudgment lies in treating MOQ decisions as purely transactional cost comparisons when they are fundamentally strategic resource allocation decisions. Every dollar committed to inventory that exceeds near-term demand is a dollar unavailable for other business needs during the holding period. The question isn't whether you saved money on the purchase. The question is what opportunities you sacrificed by having that cash locked in unsold product when market conditions required rapid response.

Procurement teams routinely calculate three cost categories when evaluating MOQ decisions: per-unit purchase price, warehousing and insurance expenses, and basic cash flow timing. These calculations capture the direct financial impact of inventory holding. What they systematically miss is the strategic opportunity cost—the value of business initiatives you cannot pursue because working capital is tied up in slow-moving stock. This isn't a hypothetical concern. It manifests in specific, measurable ways: emergency production runs you can't fund when a bestselling item stocks out, marketing campaigns you must delay because cash isn't available, competitive responses you can't execute when market conditions shift, supplier payment terms you can't negotiate because your cash position is constrained, and product development initiatives that stall because discretionary spending is frozen.

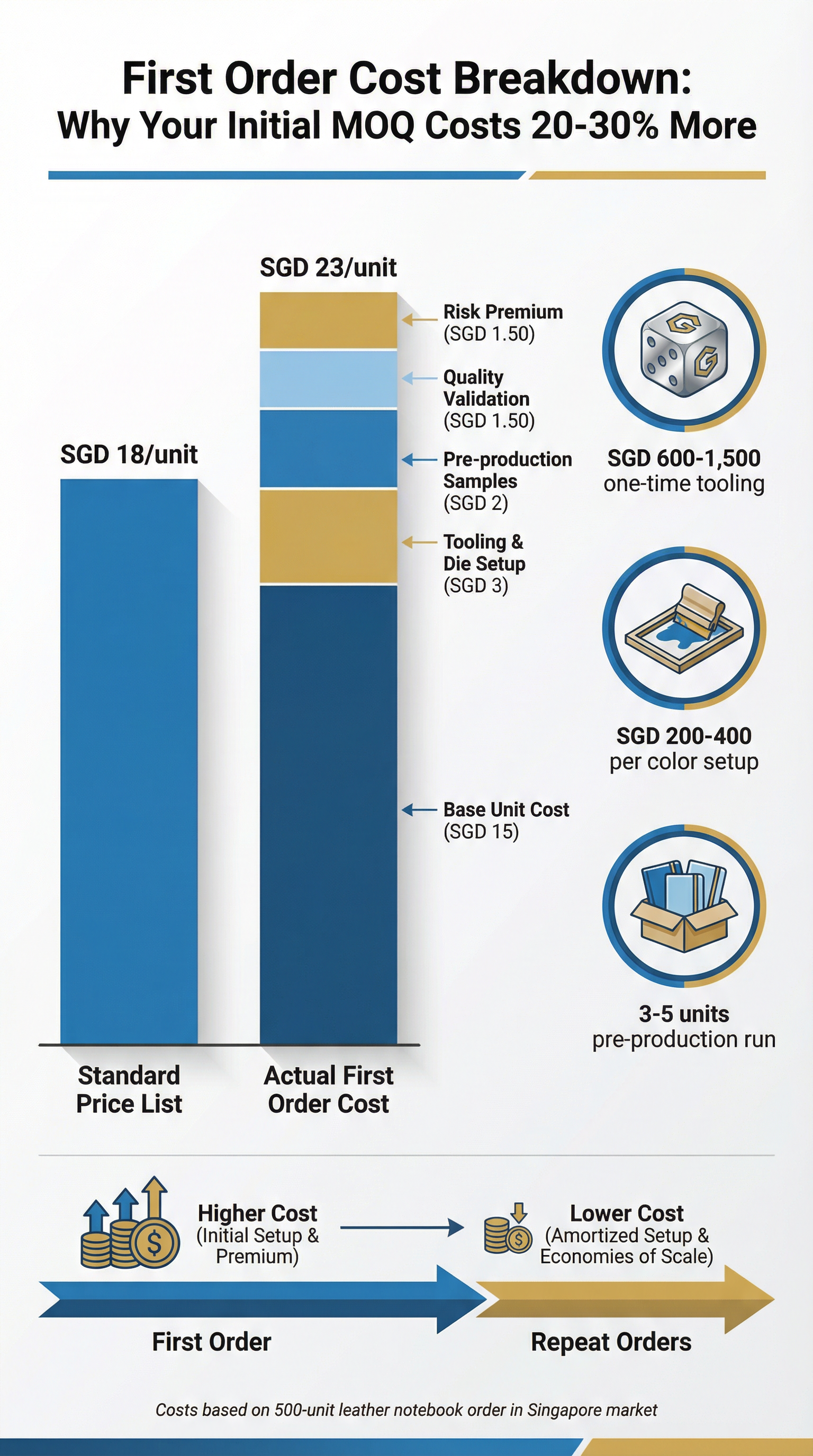

The financial impact of these missed opportunities typically exceeds the original MOQ discount by a factor of five to fifteen. A procurement decision that saves $3,000 on unit cost can easily result in $20,000 to $45,000 in lost revenue or increased expenses over the subsequent twelve months. Yet these costs remain invisible in standard procurement metrics because they don't appear as line items on purchase orders or inventory reports. They show up as missed sales targets, delayed product launches, or competitive market share losses—outcomes that procurement teams rarely connect back to MOQ decisions made months earlier.

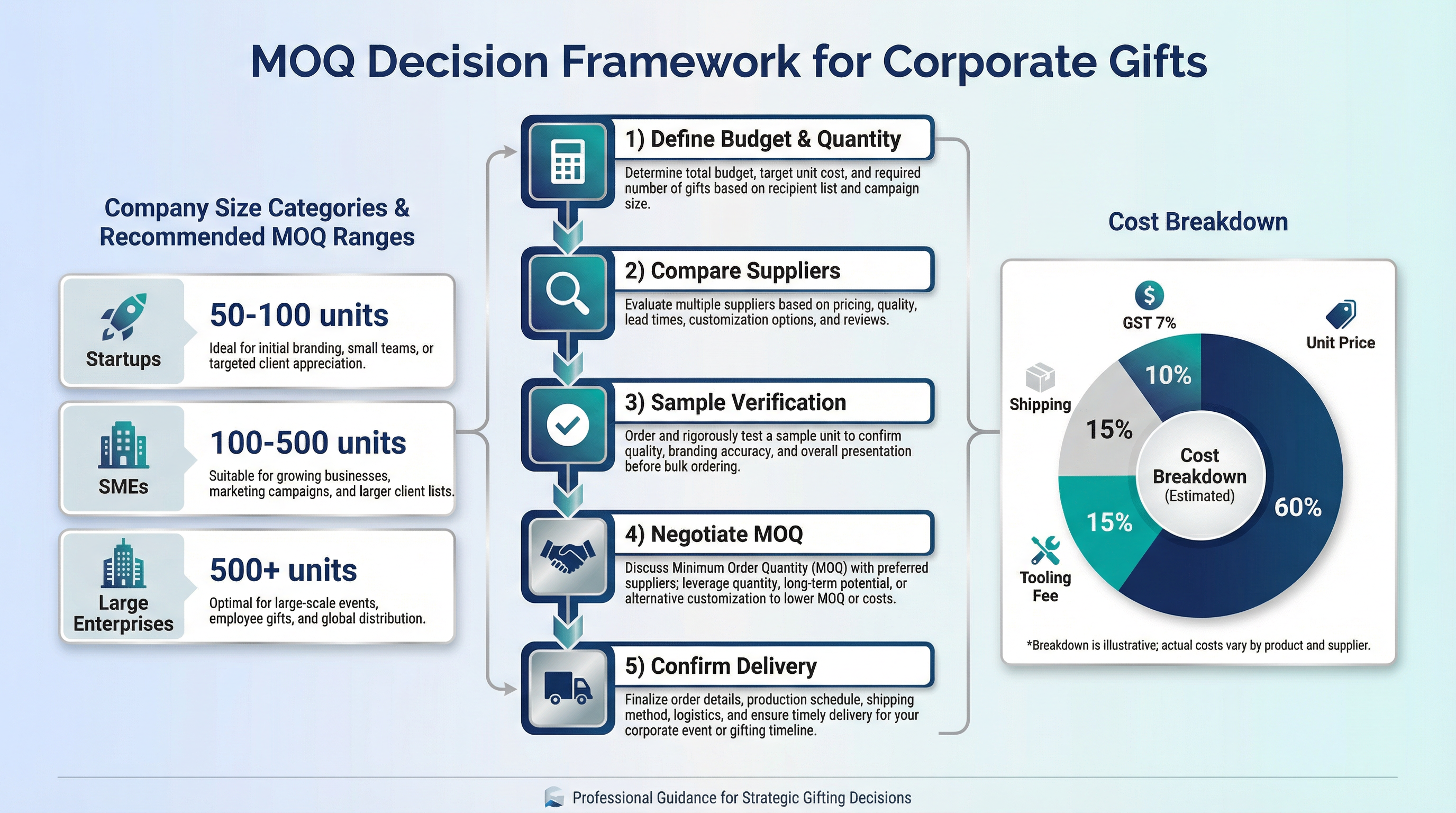

Understanding minimum order quantities for corporate gifts in Singapore requires recognizing that MOQ isn't just a supplier requirement that affects unit economics—it's a strategic constraint that determines how much working capital you'll have available for market responsiveness over the next six to eighteen months. The most effective procurement strategy isn't to minimize per-unit cost. It's to optimize the balance between purchase price efficiency and strategic flexibility, ensuring your company retains enough liquid capital to respond to market opportunities and competitive threats as they emerge.

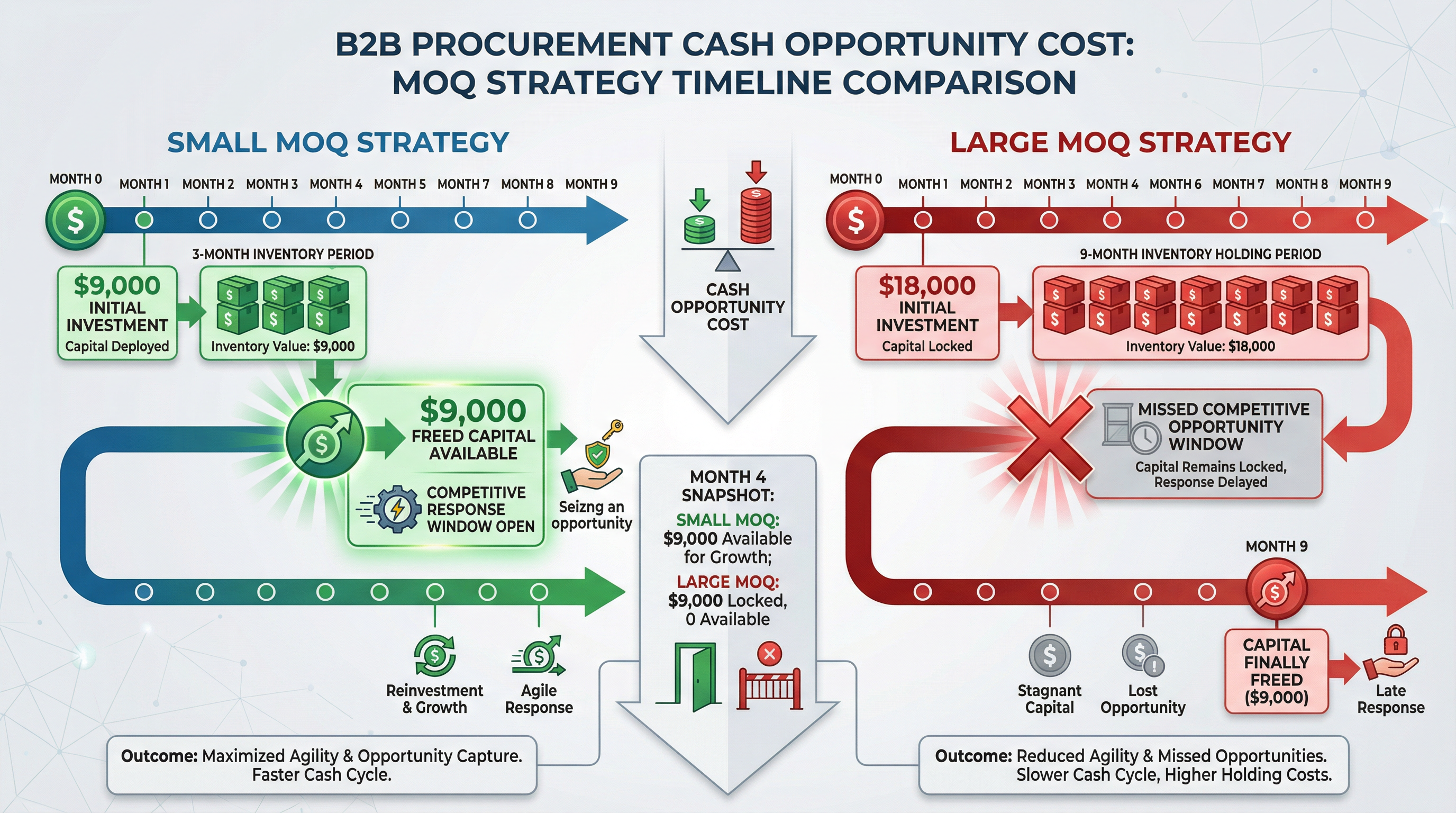

Consider how this dynamic plays out in practice. Your company operates with $85,000 in discretionary working capital—cash available for non-committed expenses after accounting for payroll, rent, and contractual obligations. You place an order for 1,200 corporate gift notebooks at $15 per unit to meet a supplier's MOQ, committing $18,000. Your sales forecast projects selling 500 units over the next three months, with the remaining 700 units moving over the subsequent six months based on historical seasonal patterns. This forecast proves accurate for the first three months. You sell 480 units, converting $7,200 of inventory back to cash. Your working capital position is now $74,200: the original $85,000 minus the $18,000 purchase, plus the $7,200 from sales.

In month four, two events occur simultaneously. First, your bestselling leather portfolio—a different product line—experiences unexpected demand surge due to a corporate client's bulk order program. Your supplier can fulfill a rush production run of 300 units, but requires $12,000 upfront payment with a three-week lead time. Second, a competitor launches a notebook line with similar specifications at a 15% lower price point. Your sales team identifies an opportunity to counter this with a limited-time promotional bundle: buy two notebooks, receive a branded pen set. The promotion requires $8,500 to fund: $3,500 for pen set inventory, $2,500 for promotional materials, and $2,500 for digital advertising to announce the offer.

You now face a strategic constraint. Funding both the portfolio production run and the promotional campaign requires $20,500. Your available working capital is $74,200, but $10,500 of that is already allocated to next month's supplier payments for other product lines. Your effective discretionary cash is $63,700. Technically, you have enough to fund both initiatives. But your finance director flags a risk: if you commit $20,500 now, your cash buffer drops to $43,200. If any customer payments are delayed by more than two weeks—a common occurrence—you won't have enough cash to cover payroll in six weeks without drawing on your credit line, which carries an 8.5% annual interest rate.

The decision comes down to priorities. You can fund the portfolio production run, which has a confirmed purchase order and will generate $18,000 in revenue within 45 days. Or you can fund the promotional campaign, which might stabilize notebook sales but has no guaranteed return. You cannot fund both without accepting unacceptable financial risk. The promotional campaign is delayed. Over the next eight weeks, your competitor's lower-priced notebooks capture 22% of your target market segment. When your promotion finally launches in month six, you recover some ground, but the damage is done. Your notebook line's revenue for the year comes in 18% below forecast, representing $31,000 in lost sales.

The root cause of this outcome traces directly back to the MOQ decision in month one. If you had accepted Supplier A's 500-unit MOQ at $18 per unit, your initial cash commitment would have been $9,000 instead of $18,000. After three months of sales, your working capital position would have been $83,200 instead of $74,200—a difference of $9,000. That additional $9,000 in available cash would have been sufficient to fund both the portfolio production run and the promotional campaign without creating payroll risk. The $3,600 you saved by accepting the larger MOQ cost you $31,000 in lost notebook revenue, plus the strategic disadvantage of ceding market position to a competitor during a critical product launch window.

This pattern—trading short-term unit cost savings for long-term strategic constraints—emerges most clearly in three specific scenarios. The first is seasonal demand volatility. Corporate gift procurement follows predictable seasonal patterns: elevated demand in Q4 for year-end gifting, moderate demand in Q2 for mid-year events, and lower demand in Q1 and Q3. If you accept a large MOQ in Q1 to secure a volume discount, you're committing cash during a low-demand period to inventory that won't convert to revenue until Q4. That cash is unavailable for nine months—precisely the period when you need working capital flexibility to fund product development, hire seasonal staff, or invest in marketing campaigns that will drive Q4 sales. The unit cost savings from the MOQ become irrelevant if you can't afford to execute the marketing strategy that would actually move the inventory.

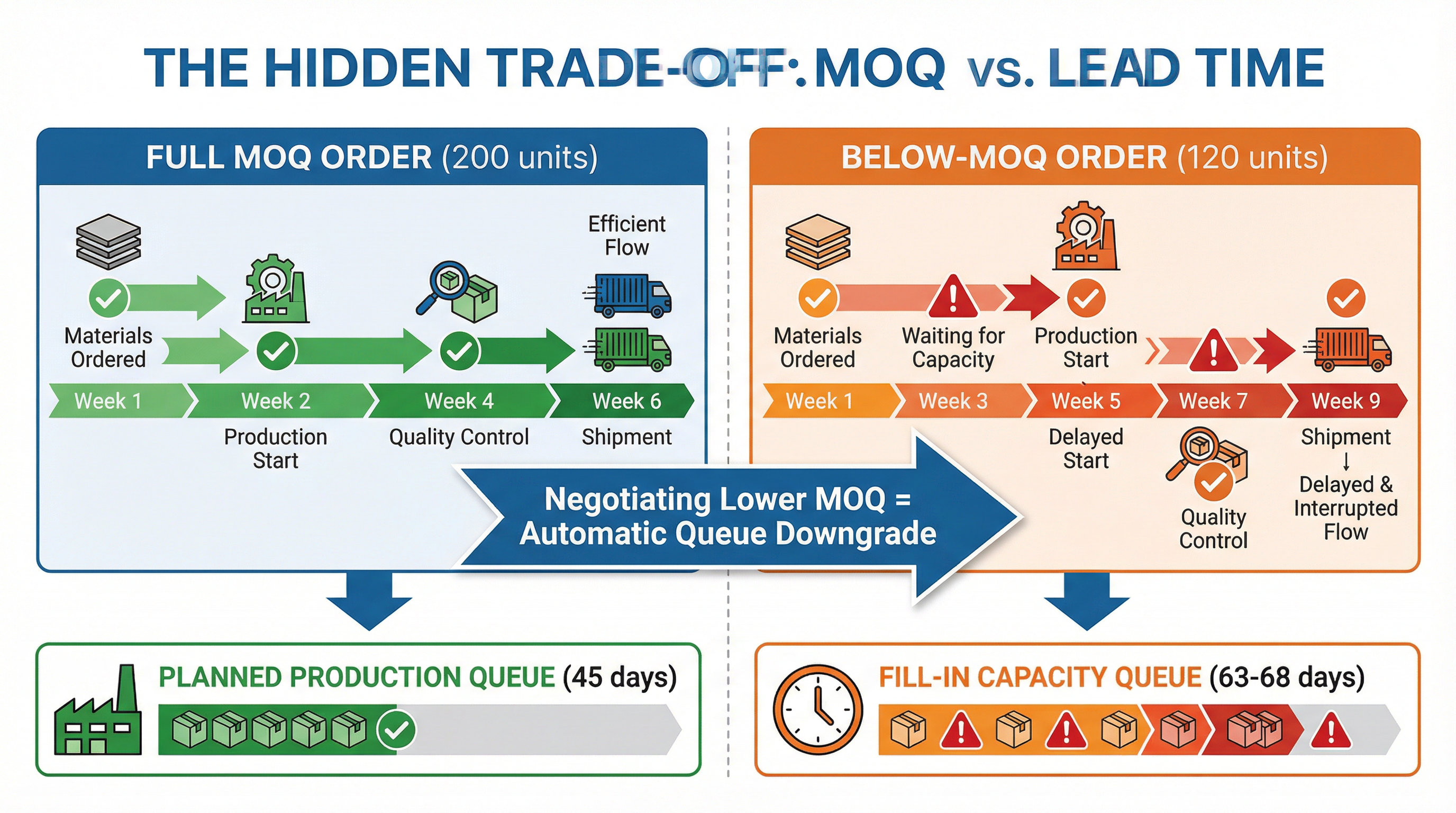

The second scenario is competitive market dynamics. B2B markets for corporate gifts are characterized by rapid product cycles and frequent competitive repositioning. A supplier launches a new material finish. A competitor introduces a lower-priced alternative. A major client changes their gifting policy to prioritize sustainability. Each of these events creates a window—typically 60 to 90 days—during which companies can respond with product adjustments, promotional offers, or targeted sales campaigns. Responding effectively requires available cash: to fund sample production, to purchase promotional inventory, to invest in sales collateral. If your working capital is tied up in slow-moving MOQ inventory, you can't respond during that window. By the time your inventory converts to cash, the competitive opportunity has closed. Your competitors have secured the new client relationships, and you're left trying to win back market share at a disadvantage.

The third scenario is supplier relationship leverage. Procurement teams understand that payment terms are negotiable: 30-day net terms can sometimes be extended to 45 or 60 days, particularly if you're a reliable customer with a strong payment history. But this negotiation requires leverage, and leverage requires options. If your cash position is constrained because working capital is tied up in MOQ inventory, you lose negotiating power. You can't credibly threaten to switch suppliers or to reduce order volumes because you need those extended payment terms just to maintain cash flow. Suppliers recognize this dynamic. They're less likely to offer favorable terms to buyers whose cash position appears tight. The MOQ decision you made six months ago—committing excess cash to inventory—directly weakens your negotiating position in current supplier discussions, resulting in less favorable terms that compound your cash constraints over time.

The financial impact of these scenarios can be quantified through a framework that procurement teams rarely apply: opportunity cost analysis. This requires calculating not just what you spent on MOQ inventory, but what you could have earned or saved if that cash had remained available for other uses. The calculation has four components. First, direct revenue opportunity cost: identify specific sales opportunities that were delayed or lost because cash was unavailable. In the notebook example, this was $31,000 in lost sales from delayed competitive response. Second, operational efficiency cost: calculate additional expenses incurred because you couldn't optimize operations. This includes rush shipping fees paid because you couldn't fund advance inventory purchases, overtime labor costs because you couldn't hire additional staff, or credit line interest charges because you had to borrow to cover short-term cash gaps. Third, supplier negotiation cost: estimate the value of payment terms or volume discounts you couldn't secure because your cash position limited negotiating leverage. This is harder to quantify but typically ranges from 2% to 5% of annual supplier spend. Fourth, strategic initiative cost: assess the impact of delayed or canceled projects—product development, market expansion, technology investments—that would have generated long-term value but couldn't be funded because working capital was constrained.

When you sum these four components, the total opportunity cost of an MOQ decision typically ranges from three to eight times the original unit cost savings. A $3,000 discount that requires tying up $15,000 in excess inventory for nine months routinely results in $12,000 to $24,000 in opportunity costs. The exact multiplier depends on your industry's competitive dynamics, your company's growth stage, and the specific market conditions during the inventory holding period. But the directional pattern is consistent: MOQ decisions that optimize for unit cost savings systematically underperform MOQ decisions that optimize for strategic flexibility.

Procurement teams resist this analysis for two reasons. First, opportunity costs are inherently counterfactual. You're calculating the value of opportunities you didn't pursue, which requires making assumptions about what would have happened if you had made different decisions. This feels speculative compared to the concrete certainty of per-unit cost savings. Second, opportunity costs are distributed across multiple budget categories and time periods. The lost notebook revenue shows up in sales reports. The delayed marketing campaign shows up in marketing budgets. The supplier negotiation disadvantage shows up in next quarter's procurement costs. No single report captures the full impact, so the connection back to the original MOQ decision remains invisible unless someone deliberately constructs the analysis.

But the difficulty of measurement doesn't reduce the reality of the cost. Your company's financial performance over a twelve-month period is determined by the sum of all decisions made during that period, including decisions about how to allocate working capital. If you systematically prioritize unit cost savings over strategic flexibility in MOQ decisions, you systematically constrain your ability to respond to market opportunities and competitive threats. This constraint compounds over time. Each MOQ decision that ties up excess cash makes the next decision more constrained, because you have less working capital available. Within 18 to 24 months, companies can find themselves in a position where nearly all discretionary cash is tied up in slow-moving inventory purchased to meet various MOQ requirements, leaving almost no flexibility for strategic initiatives. At that point, the cumulative opportunity cost can exceed the company's annual operating profit.

The solution isn't to avoid MOQs entirely. Many MOQ requirements are reasonable and align well with demand patterns. The solution is to evaluate MOQ decisions through a strategic lens rather than a purely transactional lens. This requires asking three questions before accepting any MOQ commitment. First, how long will this inventory remain unsold? Calculate expected inventory turns based on historical sales velocity and seasonal patterns. If the MOQ exceeds three months of projected demand, the excess inventory will tie up cash for at least six months, possibly longer. Second, what is our projected cash position over the next six months? Review your cash flow forecast to identify periods when working capital might be constrained. If you're entering a period of high cash needs—seasonal hiring, major marketing campaigns, equipment purchases—committing excess cash to MOQ inventory during that period creates strategic risk. Third, what is the opportunity cost of having this cash unavailable? Consider specific initiatives your company might need to fund over the next six to nine months: competitive responses, product development, market expansion. Estimate the value of those initiatives and compare it to the unit cost savings from the MOQ.

If the opportunity cost exceeds the unit cost savings by a factor of three or more, the MOQ commitment is strategically unsound regardless of how attractive the per-unit discount appears. You're trading a small certain gain for a large potential loss. The more volatile your market, the more important this calculation becomes. In stable markets with predictable demand, MOQ decisions carry less strategic risk because the likelihood of needing rapid cash deployment is lower. In dynamic markets with frequent competitive shifts, MOQ decisions carry substantial strategic risk because the likelihood of needing rapid cash deployment is high.

This analysis reveals why the most successful procurement teams don't optimize for lowest unit cost. They optimize for lowest total cost of ownership while maintaining strategic flexibility. This sometimes means accepting higher per-unit prices to preserve working capital availability. It sometimes means negotiating staggered delivery schedules that spread MOQ commitments over multiple months, reducing the peak cash requirement. It sometimes means walking away from attractive volume discounts because the cash commitment required would constrain strategic options during a critical business period. These decisions appear suboptimal when evaluated purely on unit economics. They prove optimal when evaluated on total business performance over a twelve-month horizon, because they preserve the company's ability to respond to opportunities and threats as they emerge.

The procurement function's role isn't to minimize purchase costs. It's to optimize resource allocation in support of business strategy. MOQ decisions are resource allocation decisions. Every dollar committed to inventory is a dollar unavailable for other uses. The question isn't whether you're getting a good price. The question is whether committing that cash to inventory right now, in this quantity, is the best use of your company's limited working capital given your strategic priorities and market conditions over the next six to twelve months. When procurement teams start asking that question—and demanding data to answer it rigorously—MOQ decisions shift from transactional cost optimization to strategic resource allocation. That shift typically improves overall business performance by 8% to 15% annually, as companies gain the financial flexibility to pursue high-value opportunities that would otherwise remain out of reach due to cash constraints created by well-intentioned but strategically misaligned MOQ commitments.

Related Articles

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks