The production manager called at 2:47 PM on a Thursday, six weeks into what should have been an eight-week manufacturing cycle for your corporate gift box order. The leather portfolio supplier you selected after three months of negotiations had seemed perfect during the MOQ discussions—they agreed to 800 units when their standard minimum was 1,200, quoted a competitive price, and promised delivery in time for your October client appreciation event. The sampling went smoothly, the deposit cleared without issue, and your procurement team marked the project as low-risk in the quarterly review.

Now the production manager is explaining that the embossing equipment can only process 45 units per day instead of the 120 units per day the sales team quoted during negotiations. At that rate, your 800-unit order requires seventeen production days, not the seven days originally calculated. But the embossing line is also handling orders for two other clients, which means your production slots are scattered across a six-week window instead of a continuous run. The earliest possible completion date is now mid-November, three weeks after your event. The supplier is very sorry about the confusion. The sales team apparently didn't consult with production before accepting the order.

Your procurement manager insists this situation is unforeseeable. The supplier provided employee headcount, machine specifications, and facility square footage during the initial discussions. They showed ISO 9001 certification and shared photos of their production floor. They accepted the 800-unit MOQ without hesitation, which your team interpreted as confirmation they had adequate capacity. How could anyone have predicted that the sales team would commit to an order without verifying production capability?

This scenario repeats itself in corporate gift procurement every quarter, and the root cause is always the same timing error. Buyers conduct capacity verification after MOQ commitment, not before. The purchase order gets signed, the deposit gets paid, and only then does anyone ask detailed questions about production throughput, equipment availability, or scheduling constraints. By that point, the buyer has surrendered all negotiation leverage. The supplier has your money, your timeline is locked, and your options have narrowed to accepting delays or scrambling to find alternative sources while eating the sunk costs.

Capacity verification timing determines whether buyers maintain leverage to address constraints before commitment or discover problems after losing negotiation power.

The standard procurement sequence treats capacity verification as a production-phase activity rather than a negotiation-phase prerequisite. The MOQ discussion focuses entirely on order quantity and unit price. Can the supplier accept 800 units instead of their standard 1,200? Will they maintain the same per-unit cost at the lower volume? If both answers satisfy the buyer's budget constraints, the negotiation concludes and the purchase order moves forward. Capacity verification, if it happens at all, occurs weeks later when production scheduling begins. This sequencing error transforms what should be a straightforward risk assessment into a crisis management exercise.

The disconnect stems from a fundamental misunderstanding about what MOQ acceptance actually signals. When a supplier agrees to produce 800 units instead of their standard 1,200-unit minimum, buyers interpret this as confirmation that the supplier has evaluated their production capacity and determined they can execute the order profitably. The logic seems sound: why would a supplier accept an order they cannot fulfill? This assumption ignores the powerful incentives that drive suppliers to say yes first and solve problems later.

For suppliers, especially those competing for new business or trying to fill production gaps during slow seasons, turning down an order carries immediate costs. The potential client might never return. The production slots might remain empty. The sales team's quarterly targets might slip. These pressures create a strong bias toward acceptance, even when production capacity is uncertain or requires optimistic assumptions about equipment uptime, labor availability, or process efficiency. The supplier genuinely believes they can make it work, or at least believes they can figure it out once the order is confirmed and the deposit is secured.

This dynamic intensifies in markets where cultural norms discourage direct refusal. In many East Asian manufacturing contexts, saying no to a potential client is considered impolite or damaging to the relationship. A supplier facing a capacity constraint is more likely to accept the order and then work to expand capacity, adjust schedules, or find workarounds than to explicitly state that the requested volume exceeds their current capability. The buyer, unaware of these cultural communication patterns, takes the acceptance at face value and proceeds with contracting.

The capacity verification that does occur during MOQ negotiations typically relies on surface-level metrics that bear little relationship to actual production capability. The supplier reports they have 200 employees and 50 machines. The buyer calculates that this should be more than adequate for an 800-unit order and moves forward. This calculation ignores every variable that actually determines whether those 200 employees and 50 machines can deliver 800 units on schedule.

Employee headcount means nothing without understanding skill levels, training depth, turnover rates, and absenteeism patterns. A facility with 200 employees might have only 40 who are qualified to operate the specialized equipment needed for your product. If turnover is high, those 40 might include 15 new hires still in training. If absenteeism runs at 8-10% during peak production months, effective capacity drops further. The supplier's sales team quotes capacity based on full staffing at full productivity, but production reality operates under constraints the sales team never mentions because they genuinely don't track them.

Machine count suffers from similar disconnects. Fifty machines sounds impressive until you learn that twelve are down for maintenance, eight are dedicated to a long-term contract with another client, and fifteen are the wrong type for your product specifications. The remaining fifteen machines might theoretically handle your order, but only if they run at optimal efficiency with minimal downtime, perfect material flow, and no quality issues requiring rework. Production managers know that optimal efficiency is a planning assumption, not an operational reality, but this nuance rarely makes it into the sales presentations that inform MOQ negotiations.

The gap between theoretical capacity and actual throughput widens further when quality control enters the picture. A supplier might genuinely be able to produce 120 embossed portfolios per day if quality standards are loose and defect rates are acceptable at 15-20%. But if your specifications require defect rates below 2%, the effective throughput might drop to 45 units per day once you account for inspection time, rework cycles, and the occasional need to scrap entire batches when process parameters drift. The supplier's capacity claims during MOQ negotiations almost never include these quality-adjusted throughput figures because doing so would make their capacity appear inadequate and risk losing the order.

Supply chain dependencies create another layer of capacity risk that MOQ discussions systematically ignore. Your 800-unit leather portfolio order might require custom-dyed leather panels from an upstream tannery. The portfolio manufacturer has adequate assembly capacity, but the tannery can only produce 200 panels per week in your specified color. This means your order, even though it's well within the portfolio manufacturer's assembly capacity, is actually constrained by the tannery's dyeing capacity. The portfolio manufacturer knows this, but during MOQ negotiations they focus on their own capacity and assume they can manage the upstream constraint somehow. When production begins and the tannery can't accelerate, your delivery date slips.

Effective capacity verification requires examining equipment reality, labor capability, supply chain dependencies, and quality-adjusted throughput before MOQ commitment.

The timing of capacity verification matters because leverage exists only before commitment. When you're negotiating MOQ and the supplier is trying to win your business, you have the power to ask detailed questions, request documentation, and walk away if the answers don't satisfy you. The supplier has every incentive to provide accurate information because overpromising at this stage risks losing credibility if problems emerge later. But this window of leverage closes the moment you sign the purchase order and transfer the deposit. At that point, the supplier has your money, your timeline pressure is their negotiating advantage, and your options have narrowed dramatically.

Consider the difference in supplier responses to capacity questions asked at different stages. During MOQ negotiation, when you ask about embossing capacity, the supplier might admit that their current equipment can handle 45 units per day but they're planning to add a second embossing line next month that will double capacity. This gives you the option to delay your order until the new equipment is operational, negotiate a longer lead time, or look for alternative suppliers. The same question asked after you've signed the PO and paid the deposit gets a very different response. The supplier acknowledges the capacity constraint but frames it as a scheduling challenge they're working to resolve. Your leverage to walk away is gone, so the conversation shifts to damage control rather than informed decision-making.

The production planning capabilities that determine whether a supplier can actually execute your order are almost never evaluated during MOQ negotiations. A supplier might have adequate equipment and labor in aggregate, but if their production planning systems are weak, they'll struggle to coordinate material flow, balance workloads across different product lines, and respond to the inevitable disruptions that occur during any manufacturing cycle. Poor planning turns theoretical capacity into actual chaos, but buyers don't discover this until production is underway and problems start surfacing.

This planning capability gap becomes especially problematic for suppliers handling high-mix, low-volume production. Your 800-unit corporate gift order might be one of fifteen different products the supplier is manufacturing simultaneously, each with different specifications, materials, and quality requirements. Effective capacity in this environment depends entirely on how well the supplier can schedule changeovers, minimize setup times, and prevent cross-contamination between product lines. A supplier with strong equipment and weak planning will consistently underperform their theoretical capacity, but this weakness only becomes visible during execution.

The financial pressure suppliers face to accept orders they cannot comfortably execute intensifies during slow periods. A supplier experiencing a temporary demand gap might accept your 800-unit order even though it stretches their capacity, reasoning that the revenue is better than idle equipment and underutilized labor. They genuinely intend to make it work, perhaps by extending shifts, reducing changeover frequency, or temporarily prioritizing your order over others. But these workarounds are fragile and tend to collapse when unexpected problems arise. A key employee quits, a machine breaks down, or another client demands schedule acceleration, and suddenly your order is the one that gets delayed because you're the client with the least leverage.

The risk of unauthorized subcontracting emerges directly from this capacity-commitment mismatch. When a supplier realizes mid-production that they cannot meet your delivery date with their own facilities, they face a choice: admit the problem and negotiate a delay, or quietly subcontract part of the work to another facility and hope you don't notice. Many suppliers choose the latter, reasoning that delivering on time, even if it means using an unapproved subcontractor, is better than admitting they overcommitted. The quality and consistency risks this creates are substantial, but the buyer doesn't discover the subcontracting until quality problems emerge or an audit reveals the arrangement.

The cultural and communication barriers that prevent suppliers from saying no during MOQ negotiations persist throughout the production cycle, making it difficult for buyers to get accurate status updates even after problems emerge. A supplier facing a capacity shortfall is more likely to provide optimistic progress reports and vague reassurances than to explicitly state that delivery will be late. The buyer, relying on these progress reports for their own planning, doesn't realize there's a problem until the scheduled delivery date passes with no shipment. By then, the options for mitigation are extremely limited.

The organizational structure within procurement teams often reinforces this timing error. The team negotiating MOQ and price is measured on cost savings and contract terms, not on production risk assessment. They lack the technical background to ask detailed capacity questions and don't have relationships with the supplier's production management. The quality and technical teams who could conduct meaningful capacity verification don't get involved until after the contract is signed, when their role shifts to monitoring execution rather than validating capability. This handoff creates a gap where capacity risk falls through.

Some buyers attempt to address capacity concerns during MOQ negotiations by asking suppliers to provide capacity declarations or production schedules. These documents, when provided, are almost always optimistic projections rather than conservative commitments. A supplier will show you a production schedule indicating your 800-unit order will be completed in seven days, but that schedule assumes perfect conditions: no equipment downtime, no material delays, no quality issues requiring rework, and no competing priorities from other clients. Actual production operates under Murphy's Law, not best-case assumptions, but the schedule you receive during negotiations reflects the latter.

The verification methods that would actually reveal capacity constraints require access and time that buyers rarely invest before signing purchase orders. Visiting the production facility and observing actual operations over multiple days would show you real throughput rates, changeover times, quality control rigor, and material flow efficiency. Interviewing production managers rather than sales representatives would reveal the constraints and workarounds that define actual capacity. Requesting detailed production records from recent similar orders would demonstrate whether the supplier can consistently hit the throughput rates they're claiming. But these verification activities feel premature during MOQ negotiations, when the focus is on whether the supplier will accept your order quantity, not whether they can execute it reliably.

The cost of this timing error compounds throughout the production cycle. When capacity problems emerge mid-production, the buyer faces a cascade of bad options. Accepting a delivery delay might mean missing the event or season that justified the order in the first place, turning the entire purchase into a write-off. Pushing the supplier to accelerate often results in quality compromises as they cut corners to meet the timeline. Splitting the order between multiple suppliers to reduce the capacity burden on any single facility introduces consistency risks and doubles the administrative burden. Finding an alternative supplier mid-stream means eating the sunk costs with the original supplier while paying premium rates to the replacement for rush production.

The leverage asymmetry that emerges after contract signing extends beyond schedule negotiations to quality and specification discussions. A supplier facing capacity constraints might propose specification changes that make production easier: slightly different leather thickness, simplified embossing patterns, or alternative packaging that requires less handling. During MOQ negotiations, you could reject these changes outright or use them as negotiating points. After you've committed and paid a deposit, rejecting the changes might mean accepting even longer delays, so you're pressured to compromise on specifications you originally considered non-negotiable.

The relationship damage that results from capacity-driven delivery failures often exceeds the immediate project costs. A supplier who accepts an order they cannot execute and then delivers late or with quality issues has revealed something fundamental about their business practices. They prioritize winning orders over realistic capacity assessment. Their sales and production teams don't communicate effectively. Their planning systems can't accurately forecast throughput. These are not problems that resolve themselves, which means future orders with the same supplier carry elevated risk. But buyers often don't discover these issues until after they've invested significant time and resources in the relationship.

The pattern repeats because the immediate pain of capacity failures doesn't translate into systematic process changes. The procurement team attributes the problem to this specific supplier rather than recognizing it as a symptom of verification timing errors. They switch suppliers but continue to conduct capacity verification after MOQ commitment rather than before. The new supplier, facing the same incentives to accept orders optimistically, repeats the cycle. The buyer concludes that supplier reliability is inherently unpredictable rather than recognizing that their verification timing creates the unpredictability.

The solution requires inverting the standard sequence. Capacity verification must occur before MOQ negotiation, not after purchase order signing. This means asking detailed production questions while you still have leverage to walk away. It means treating a supplier's willingness to accept your order quantity as the beginning of due diligence, not the end. It means recognizing that capacity claims without supporting evidence are marketing statements, not operational commitments.

Effective pre-commitment capacity verification focuses on evidence rather than assertions. Instead of asking how many employees the supplier has, ask for records showing actual labor utilization rates over the past six months. Instead of accepting machine count at face value, ask for equipment maintenance logs and downtime reports. Instead of relying on theoretical throughput calculations, request production records from recent orders of similar complexity. These requests might feel aggressive during initial negotiations, but they're far less disruptive than discovering capacity problems after you've committed.

The questions that reveal actual capacity differ fundamentally from the questions buyers typically ask during MOQ negotiations. Asking about bottlenecks forces the supplier to think through their entire production flow and identify the constraining resource. Asking about their worst production month in the past year reveals how they perform under stress rather than optimal conditions. Asking how they handle competing priorities when multiple orders are in production simultaneously exposes their planning and scheduling capabilities. These questions make suppliers uncomfortable because they require honest assessment rather than optimistic projections, but that discomfort is precisely why they're valuable.

The timing of these questions matters as much as their content. Asking about capacity constraints after you've expressed strong interest in placing an order creates pressure for the supplier to minimize concerns and emphasize their capability. Asking the same questions earlier in the relationship, when you're still evaluating multiple potential suppliers, creates space for more honest responses. The supplier knows that overpromising at this stage will be discovered during your evaluation process, so they have incentive to be realistic about limitations.

The verification process should extend beyond the immediate supplier to their critical sub-suppliers, especially for components or materials that are custom-made for your product. If your leather portfolio requires custom-dyed panels, the tannery's capacity is just as important as the portfolio manufacturer's assembly capacity. If the supplier is unwilling or unable to provide visibility into their upstream supply chain, that opacity itself is a risk signal. Capacity constraints at any point in the supply chain will impact your delivery, regardless of how much capacity the final assembly supplier has.

The cultural and communication challenges that make suppliers reluctant to say no during negotiations require buyers to read between the lines and probe beyond surface-level responses. When a supplier responds to capacity questions with vague reassurances rather than specific data, that's a signal. When they emphasize their commitment to making it work rather than describing their systematic approach to capacity planning, that's a signal. When they deflect detailed questions to "after we finalize the agreement," that's a signal. These patterns don't prove the supplier lacks capacity, but they indicate the need for deeper verification before commitment.

The organizational changes required to fix this timing error extend beyond procurement processes to performance metrics and team incentives. If procurement teams are measured solely on cost savings and contract terms, they'll continue to treat capacity verification as someone else's problem. If technical and quality teams don't get involved until after contracts are signed, they can't influence the supplier selection decisions that determine production risk. Aligning these functions around shared accountability for delivery performance creates the organizational foundation for better verification timing.

The relationship between MOQ negotiation and capacity verification is not sequential—it's integrated. The supplier's willingness to accept a lower minimum order quantity should trigger more intensive capacity scrutiny, not less. A supplier who readily agrees to reduce their MOQ by 30% is either desperate for business or confident they can handle the volume. Distinguishing between these scenarios requires verification that goes far beyond the surface-level discussions that typically occur during price negotiations. Understanding order quantity thresholds means recognizing that the quantity itself is only one variable in a complex production equation.

The cost of pre-commitment capacity verification is trivial compared to the cost of mid-production capacity failures. Spending an extra week asking detailed questions and reviewing production records might feel like it's slowing down the procurement process, but it's far less disruptive than discovering six weeks into production that your supplier cannot meet the delivery date. The verification investment pays for itself the first time it prevents a capacity-driven failure or identifies a supplier limitation before you've committed resources.

The shift from post-commitment to pre-commitment capacity verification requires buyers to treat supplier acceptance of their MOQ as a hypothesis to be tested rather than a confirmation to be trusted. The supplier says they can handle 800 units in eight weeks. That's a claim that requires evidence. What production records support that throughput rate? What equipment will be used? What's the planned production schedule? How will they handle quality control? What happens if a key piece of equipment breaks down? These questions feel adversarial during negotiations, but they're far less adversarial than the conversations that occur when capacity problems emerge after commitment.

The broader lesson is that procurement decisions are not purely commercial transactions to be evaluated on price and terms. They're operational commitments that depend on the supplier's ability to execute. Treating capacity verification as a production-phase activity rather than a negotiation-phase prerequisite inverts the risk allocation, giving suppliers your money and your timeline pressure before you've confirmed they can deliver. Fixing this timing error doesn't require sophisticated tools or complex processes. It requires asking the right questions at the right time, when you still have the leverage to act on the answers.

Related Articles

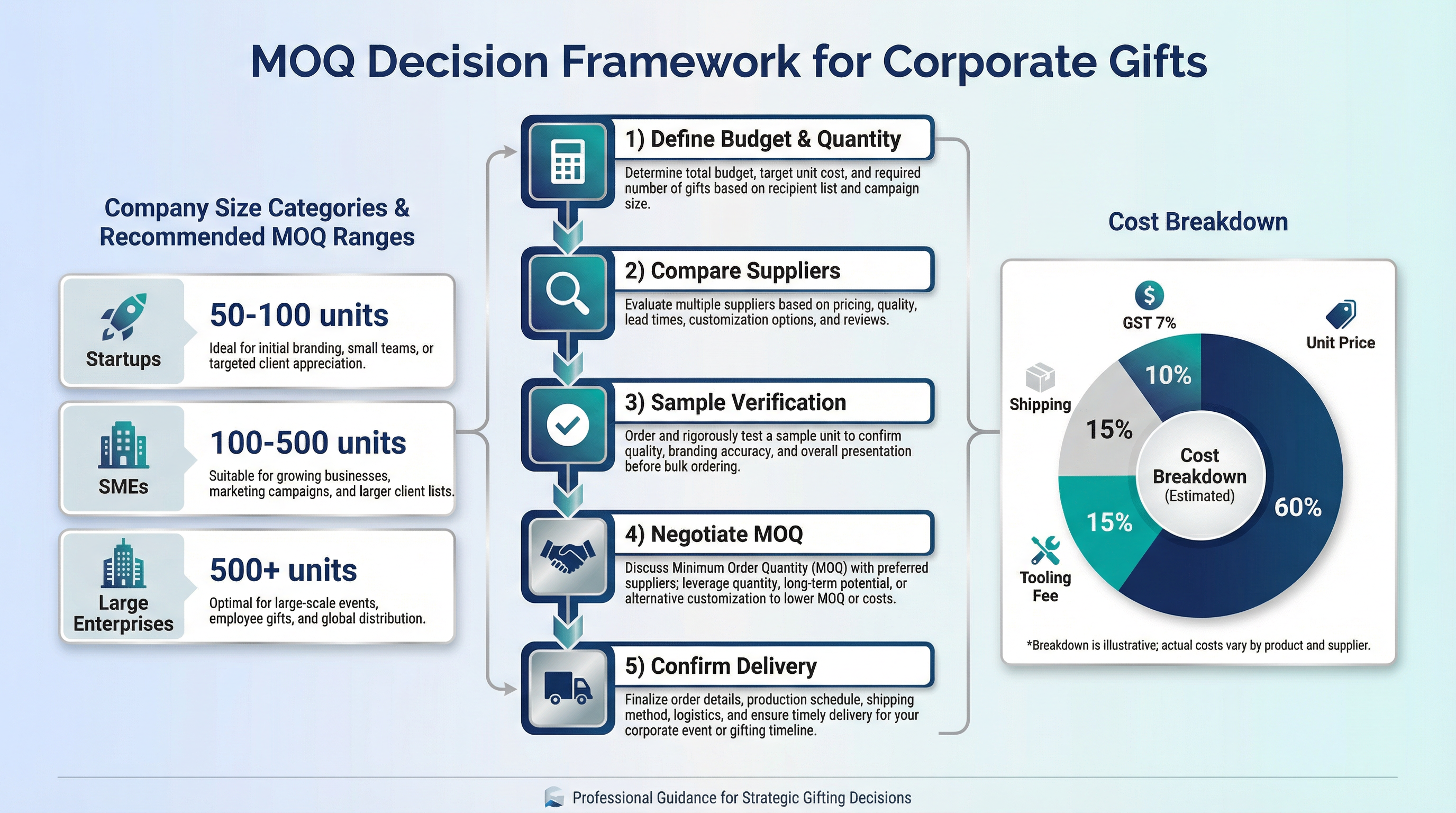

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

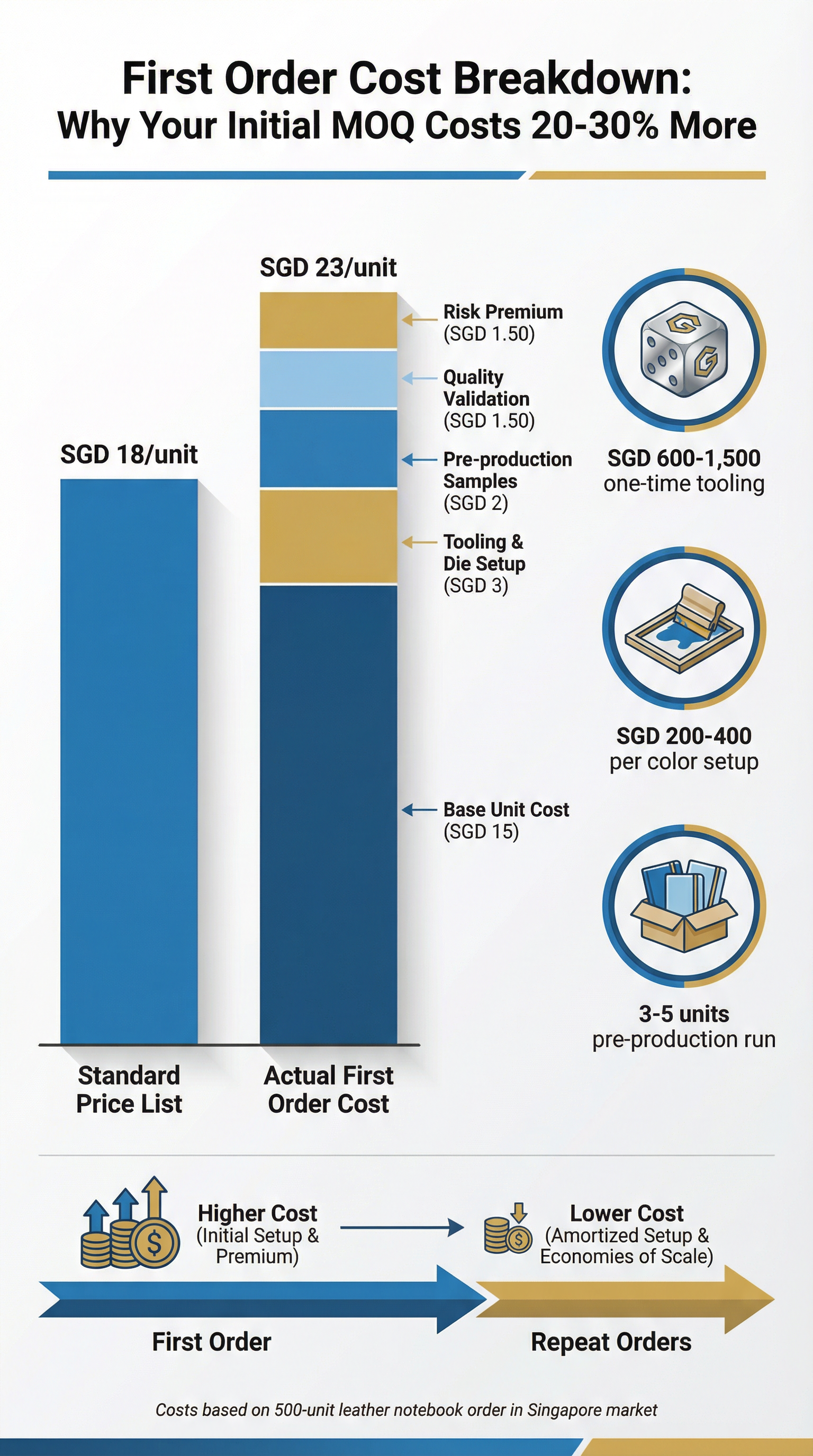

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

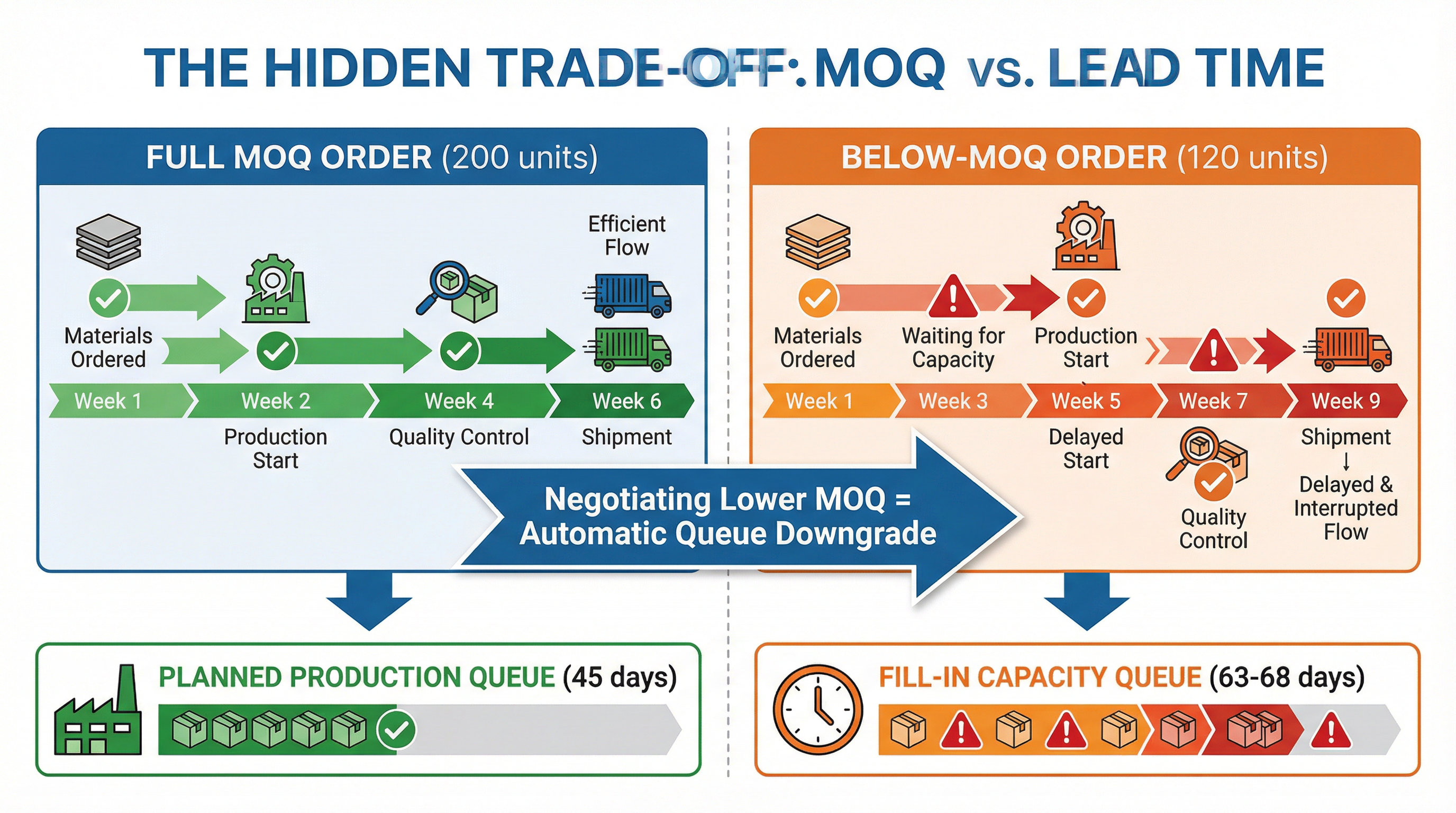

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks