When a procurement manager accepts a supplier's 1,000-unit minimum order quantity to secure a lower unit price on corporate gift boxes, the decision feels straightforward. The spreadsheet shows a 20% cost reduction per unit. The finance team approves the cash outlay. The order moves forward. What doesn't appear in that spreadsheet is the strategic position that just shifted. By committing to that MOQ, the buyer has inadvertently transferred negotiation leverage to the supplier—not for this order, but for every order that follows.

This is where MOQ decisions are consistently misjudged. The evaluation focuses entirely on the immediate transaction: unit economics, inventory levels, cash flow timing. But the MOQ commitment creates a secondary effect that compounds over time. Once a buyer has invested in tooling, completed sampling, qualified the supplier's process, and built up inventory to meet the minimum threshold, switching to an alternative source becomes prohibitively expensive. The supplier understands this dynamic far better than most procurement teams do. They know that after the first order, the buyer is locked in—not by contract, but by the accumulated switching costs that the MOQ structure created.

In practice, this is often where minimum order quantity decisions start to be misjudged. The buyer sees the MOQ as a one-time hurdle to clear for better pricing. The supplier sees it as the mechanism that converts a transactional relationship into a dependent one. Six months after that initial order, when the supplier increases prices by 12%, the buyer discovers they have no practical alternative. The cost of switching—new tooling, new sampling, inventory write-offs, production delays—exceeds the annual impact of the price increase. The supplier didn't need a long-term contract to secure the buyer's business. The MOQ structure did that automatically.

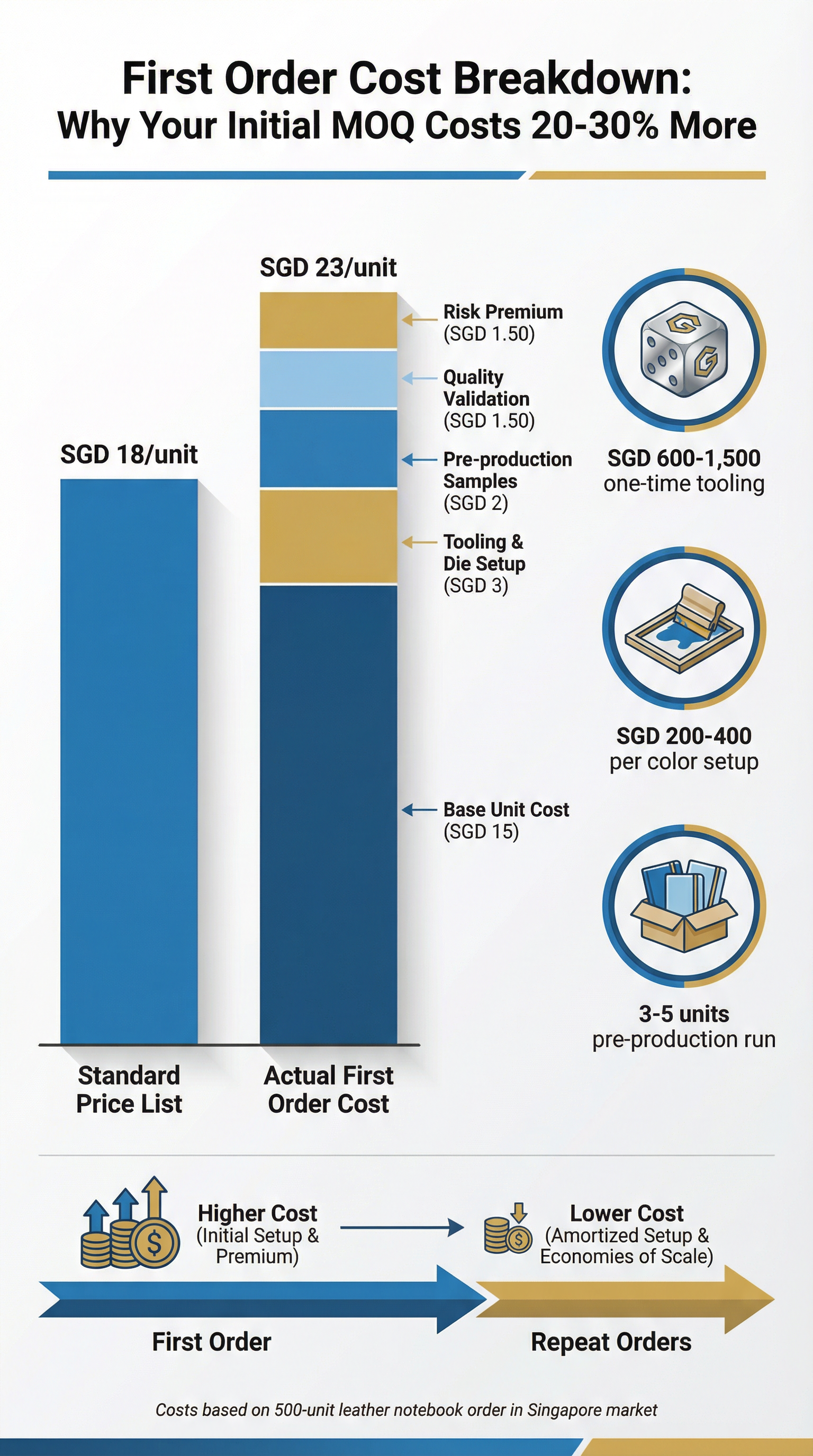

The mechanism operates through a series of irreversible commitments that accumulate during the initial MOQ fulfillment. When a buyer places their first 1,000-unit order for custom corporate gift boxes, they typically pay $3,000 to $8,000 in tooling fees for dies, molds, or printing plates. They invest another $500 to $2,000 in first article samples and approval cycles. They dedicate 2 to 4 weeks to quality validation and process qualification. And they tie up $12,000 to $15,000 in inventory to meet the minimum quantity threshold. Each of these investments is specific to that supplier's manufacturing process, material specifications, and production workflow.

The buyer treats these as sunk costs—expenses that were necessary to establish the relationship and secure favorable pricing. But from a strategic perspective, they are switching cost barriers. Every dollar spent on supplier-specific tooling is a dollar that would need to be re-spent to switch to a new manufacturer. Every week invested in process qualification is time that would need to be re-invested with an alternative source. The MOQ didn't just require a larger initial order. It required a series of commitments that make future supplier changes economically irrational.

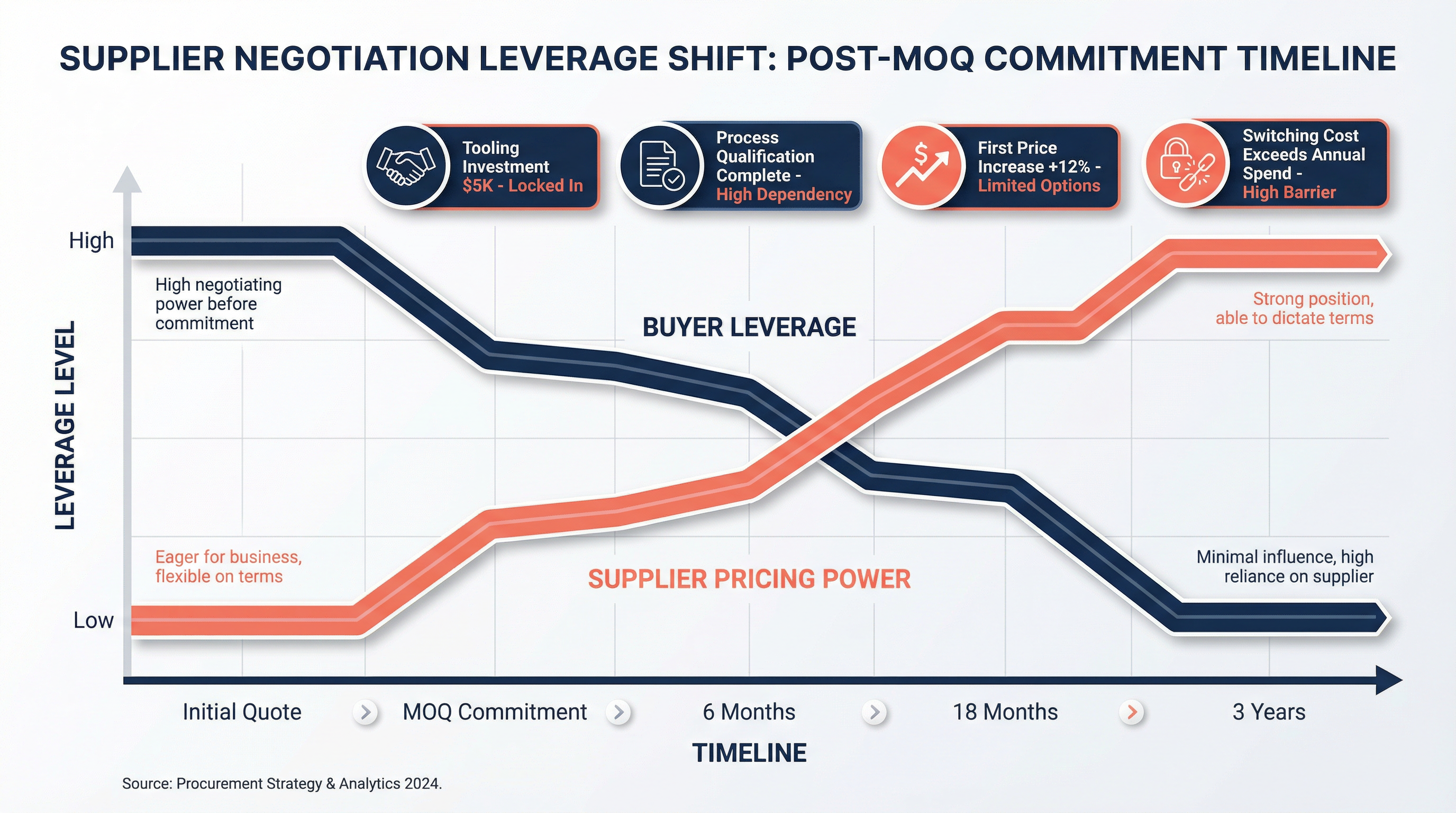

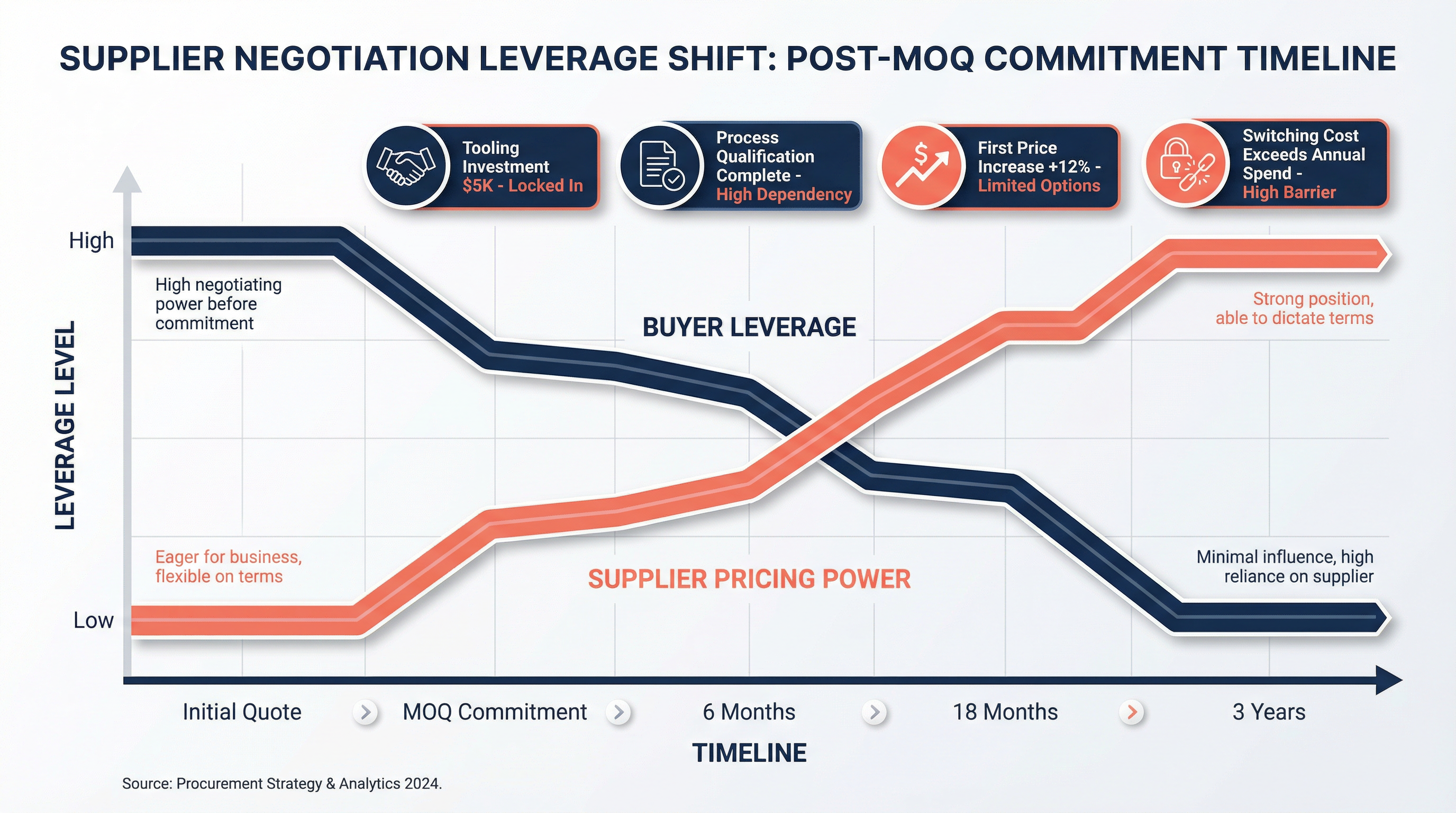

The supplier's pricing strategy reflects this understanding. The initial quote—the one that required the 1,000-unit MOQ—was competitive. It had to be, because the buyer still had alternatives. They could have chosen a different manufacturer, accepted a higher per-unit cost with a lower MOQ, or delayed the decision entirely. But once the buyer commits to that first order and completes the associated investments, the competitive landscape changes. The incumbent supplier is no longer competing against other manufacturers on equal terms. They are competing against the buyer's switching costs. And those costs are substantial.

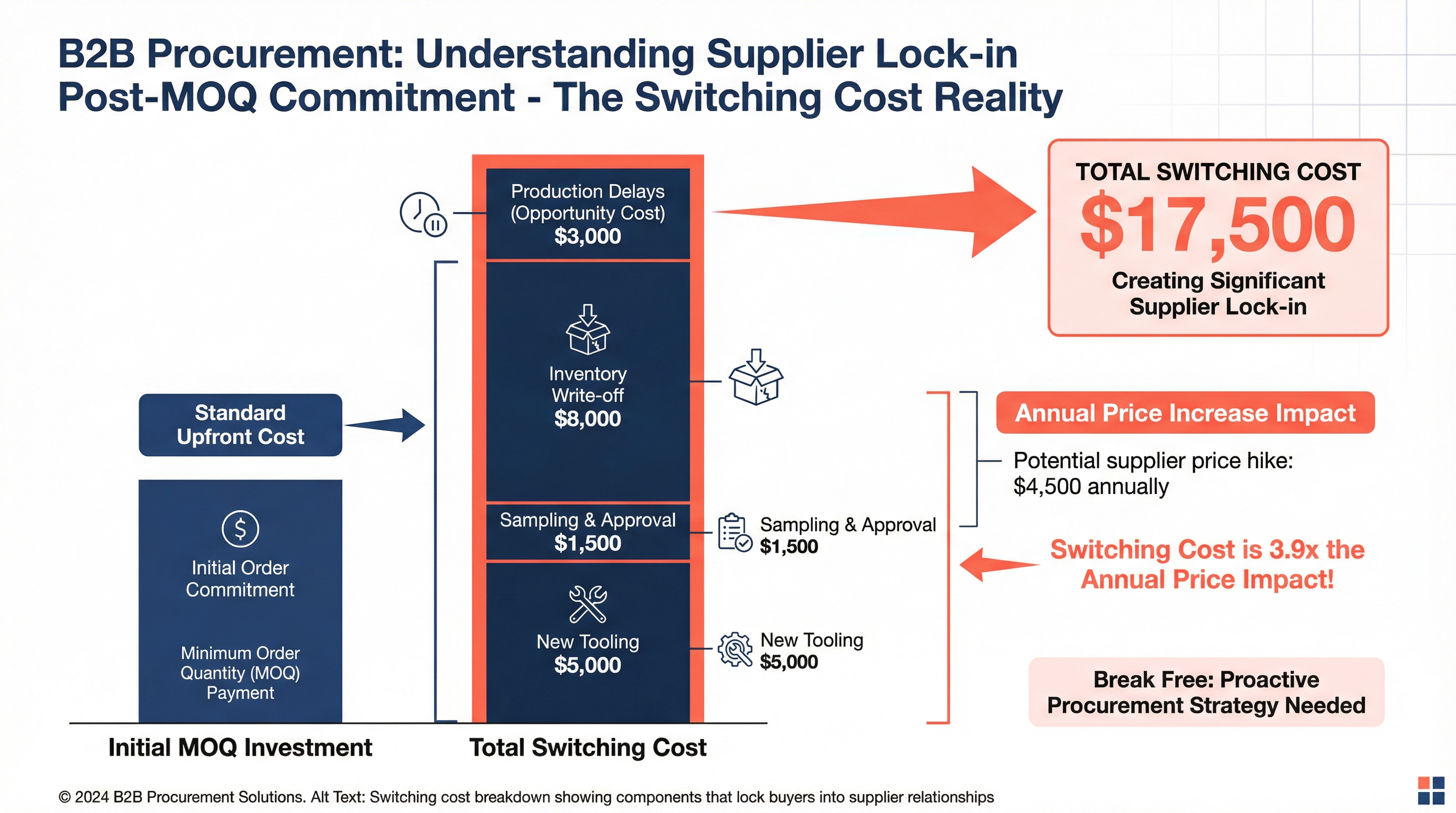

Consider the arithmetic from the buyer's perspective. Eighteen months after the initial order, the supplier announces a price increase from $12.00 per unit to $13.50 per unit—a 12.5% jump. The buyer's annual volume is 3,000 units across three orders per year. The price increase adds $4,500 to annual costs. The procurement team begins evaluating alternative suppliers. They receive quotes from two manufacturers willing to match the original $12.00 per unit price. But switching requires new tooling ($5,000), new sampling and approval ($1,500), and writing off the remaining $8,000 of inventory from the incumbent supplier. The total switching cost is $14,500.

The buyer faces a choice: accept the $4,500 annual price increase, or spend $14,500 to switch suppliers. Even if the new supplier maintains the $12.00 price indefinitely, it takes more than three years to recover the switching cost. And there's no guarantee the new supplier won't implement their own price increases once the buyer is locked in with them. The rational decision, from a purely financial perspective, is to accept the incumbent supplier's price increase. The MOQ structure ensured that outcome.

This dynamic is not unique to corporate gift procurement. It appears across any category where MOQ commitments require supplier-specific investments. Custom packaging, branded promotional items, private label products, and engineered components all follow the same pattern. The initial MOQ creates a barrier to entry that the buyer must overcome with capital investment and process qualification. Once that barrier is cleared, it becomes a barrier to exit. The supplier doesn't need to maintain competitive pricing to retain the business. They only need to keep price increases below the threshold that would justify the switching cost.

The misjudgment occurs because procurement teams evaluate MOQ decisions in isolation, as if each order is independent. They calculate the unit cost savings, assess the inventory risk, and approve the purchase. What they don't calculate is the option value they are surrendering. Before committing to the MOQ, the buyer has multiple sourcing options. They can negotiate aggressively, play suppliers against each other, or walk away if terms are unfavorable. After committing to the MOQ, those options disappear. The buyer is no longer choosing between multiple suppliers. They are choosing between an incumbent with pricing power and a costly, disruptive switching process.

The supplier's behavior changes accordingly. In the initial negotiation, they are responsive, flexible, and eager to accommodate the buyer's requirements. They offer competitive pricing, expedited sampling, and favorable payment terms. Once the MOQ commitment is made and the switching costs accumulate, that responsiveness diminishes. Price increase notifications arrive with less justification. Lead times extend. Customization requests that were previously accommodated become "non-standard" and require additional fees. The supplier is not being deliberately difficult. They are simply responding to the economic reality that the buyer no longer has practical alternatives.

The problem compounds when buyers attempt to mitigate risk by consolidating volume with a single supplier to meet higher MOQ thresholds for better pricing. The logic appears sound: if ordering 1,000 units gets a 20% discount, and ordering 2,000 units gets a 30% discount, then consolidating multiple product lines with one manufacturer maximizes cost efficiency. But this strategy accelerates the lock-in effect. Instead of being dependent on one supplier for one product, the buyer is now dependent on one supplier for multiple products. The switching cost multiplies. The supplier's pricing power increases proportionally.

This is the inverse of the order-splitting problem that procurement teams often worry about. Splitting orders across multiple suppliers to avoid individual MOQ commitments creates its own inefficiencies—duplicated tooling costs, higher per-unit pricing, increased administrative overhead. But it preserves negotiation leverage. The buyer maintains multiple qualified sources, each with their own sunk costs and process qualifications. If one supplier becomes unresponsive or implements unfavorable pricing, the buyer can shift volume to alternatives without incurring catastrophic switching costs. The unit economics may be slightly worse, but the strategic position is far stronger.

The challenge is that these trade-offs are rarely made explicit in MOQ decision frameworks. Procurement teams are measured on unit cost reduction, inventory turns, and supplier consolidation. These metrics reward the behavior that creates lock-in: accepting higher MOQs for better pricing, consolidating volume with fewer suppliers, and minimizing the administrative burden of managing multiple relationships. What they don't measure is negotiation leverage, switching cost exposure, or strategic flexibility. Those factors only become visible when the supplier exercises their pricing power and the buyer discovers they have no practical recourse.

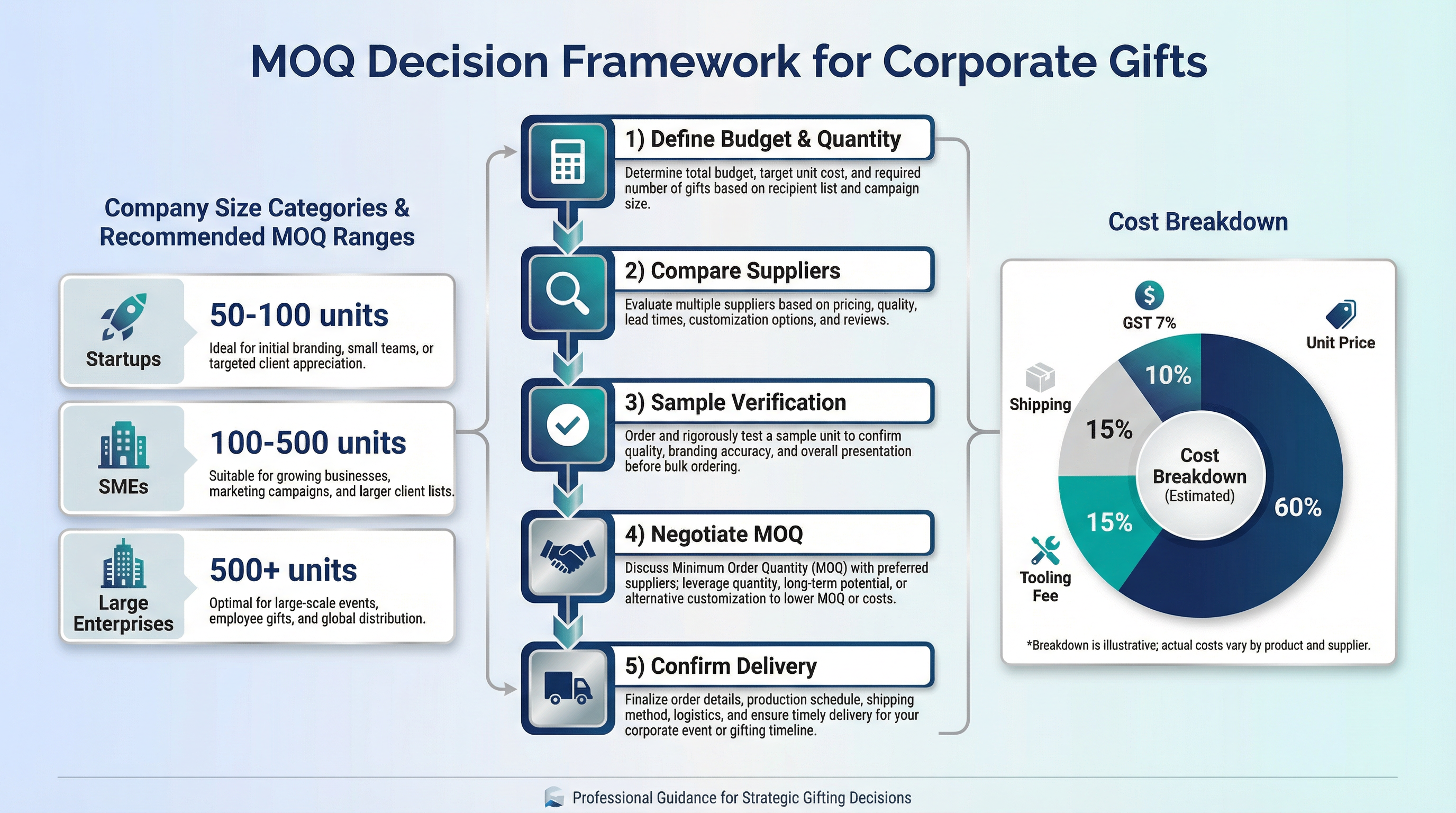

The correction requires a different evaluation framework. When assessing an MOQ commitment, the buyer should calculate not just the immediate cost impact, but the switching cost barrier being created. If the MOQ requires $10,000 in supplier-specific investments (tooling, sampling, inventory), that $10,000 becomes the minimum threshold the supplier can extract through future price increases before the buyer will consider switching. If the buyer's annual spend with that supplier is $50,000, a 20% switching cost barrier gives the supplier room to increase prices by 20% over time before triggering a sourcing change. That's a significant transfer of value that doesn't appear in the initial MOQ analysis.

A more strategic approach treats MOQ commitments as long-term partnerships that require ongoing leverage preservation. This might mean accepting slightly higher per-unit costs to maintain relationships with multiple qualified suppliers, even if one supplier offers better pricing for consolidated volume. It might mean investing in tooling with secondary suppliers before it's operationally necessary, simply to preserve the option to switch if the primary supplier's behavior changes. It might mean structuring MOQ commitments with explicit price protection clauses that limit the supplier's ability to implement increases without triggering penalty-free exit terms.

The broader principle is that MOQ decisions are not just procurement transactions. They are strategic commitments that reshape the power dynamic between buyer and supplier. The initial focus on unit cost savings obscures the longer-term impact on negotiation leverage. By the time that impact becomes visible—when the supplier announces a price increase and the buyer realizes they have no alternatives—the decision has already been made. The MOQ structure ensured it.

The pattern becomes clearer when examining how suppliers structure their MOQ tiers. A manufacturer might offer three pricing levels: $15 per unit for 500-unit orders, $12 per unit for 1,000-unit orders, and $10 per unit for 2,500-unit orders. The buyer sees this as a volume discount schedule. But the supplier is actually pricing in the switching cost barrier at each tier. The 500-unit threshold creates minimal lock-in—tooling costs are lower, inventory commitment is manageable, and the buyer could switch suppliers without catastrophic losses. The 1,000-unit threshold creates moderate lock-in—enough to make switching painful but not impossible. The 2,500-unit threshold creates severe lock-in—the accumulated investments are so substantial that the buyer would need multiple years of price increases to justify a sourcing change.

The supplier's pricing reflects this calculation. The discount from $15 to $12 per unit (20%) is larger than the discount from $12 to $10 per unit (16.7%). The supplier is willing to give up more margin to move the buyer from the 500-unit tier to the 1,000-unit tier because that transition creates the lock-in effect. Once the buyer is at 1,000 units, the incremental discount to reach 2,500 units is smaller because the lock-in already exists. The supplier is simply extracting additional volume, not creating additional dependency.

This pricing structure reveals why procurement teams often make the wrong trade-off. They see the 20% discount and calculate the annual savings: 3,000 units per year at $3 per unit savings equals $9,000 in cost reduction. That becomes the justification for accepting the 1,000-unit MOQ. What they don't calculate is the present value of future negotiation leverage. If the buyer maintains the 500-unit MOQ and preserves their ability to switch suppliers easily, they retain pricing power for every future order. The supplier knows that any price increase or service degradation could trigger an immediate sourcing change. That threat disciplines the supplier's behavior far more effectively than any contract clause.

The loss of this leverage has a quantifiable cost, though it's rarely measured. Consider a buyer who commits to the 1,000-unit MOQ and loses their ability to negotiate effectively. Over the next five years, the supplier implements cumulative price increases of 25%—well below the switching cost threshold but enough to erode the initial savings. The buyer who maintained the 500-unit MOQ and preserved their negotiation leverage experiences only 8% in price increases over the same period because the supplier knows they could lose the business at any time. The difference—17 percentage points on a $36,000 annual spend—costs the locked-in buyer $6,120 per year, or $30,600 over five years. That far exceeds the $9,000 in initial savings from accepting the higher MOQ.

The challenge is that this cost never appears in a variance report. It's not a line item that procurement can point to and say, "This is what we lost by accepting the MOQ." It manifests as a series of small price increases that seem reasonable in isolation but compound into significant value transfer over time. The buyer doesn't have a counterfactual—they don't know what pricing they could have negotiated if they had maintained their leverage. The supplier certainly isn't going to tell them. And by the time the pattern becomes obvious, the switching costs are so high that the buyer is trapped.

This is why sophisticated procurement organizations treat MOQ commitments as strategic decisions that require executive approval, not operational decisions that buyers can make independently. They recognize that accepting an MOQ is not just about inventory management or cash flow timing. It's about permanently altering the power balance in the supplier relationship. Once that balance shifts, it's extraordinarily difficult to shift it back. The supplier has no incentive to reduce their MOQ requirements after the buyer has already made the investments to meet them. And the buyer has no leverage to demand better terms because the switching costs make the threat of leaving non-credible.

The correction requires a different mental model for MOQ evaluation. Instead of asking, "Can we afford to carry this inventory?" the buyer should ask, "What is the cost of losing our ability to switch suppliers?" Instead of calculating unit cost savings, they should calculate the present value of future negotiation leverage. Instead of treating the MOQ as a one-time hurdle, they should treat it as a permanent transfer of strategic position. These questions lead to very different decisions. They might lead the buyer to accept higher per-unit costs in exchange for lower MOQs that preserve flexibility. They might lead to investments in secondary suppliers even when the primary supplier is performing well, simply to maintain the credible threat of switching. They might lead to explicit contract terms that cap price increases or provide penalty-free exit clauses if the supplier's behavior changes.

The broader lesson is that MOQ structures are not neutral. They are designed by suppliers to create dependency, and they succeed at that objective far more often than buyers realize. The initial decision to accept an MOQ feels like a straightforward trade-off: higher volume in exchange for better pricing. But the actual trade-off is far more consequential: immediate cost savings in exchange for permanent loss of negotiation leverage. By the time the buyer understands what they gave up, the decision is irreversible. The MOQ structure ensured it.

Related Articles

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

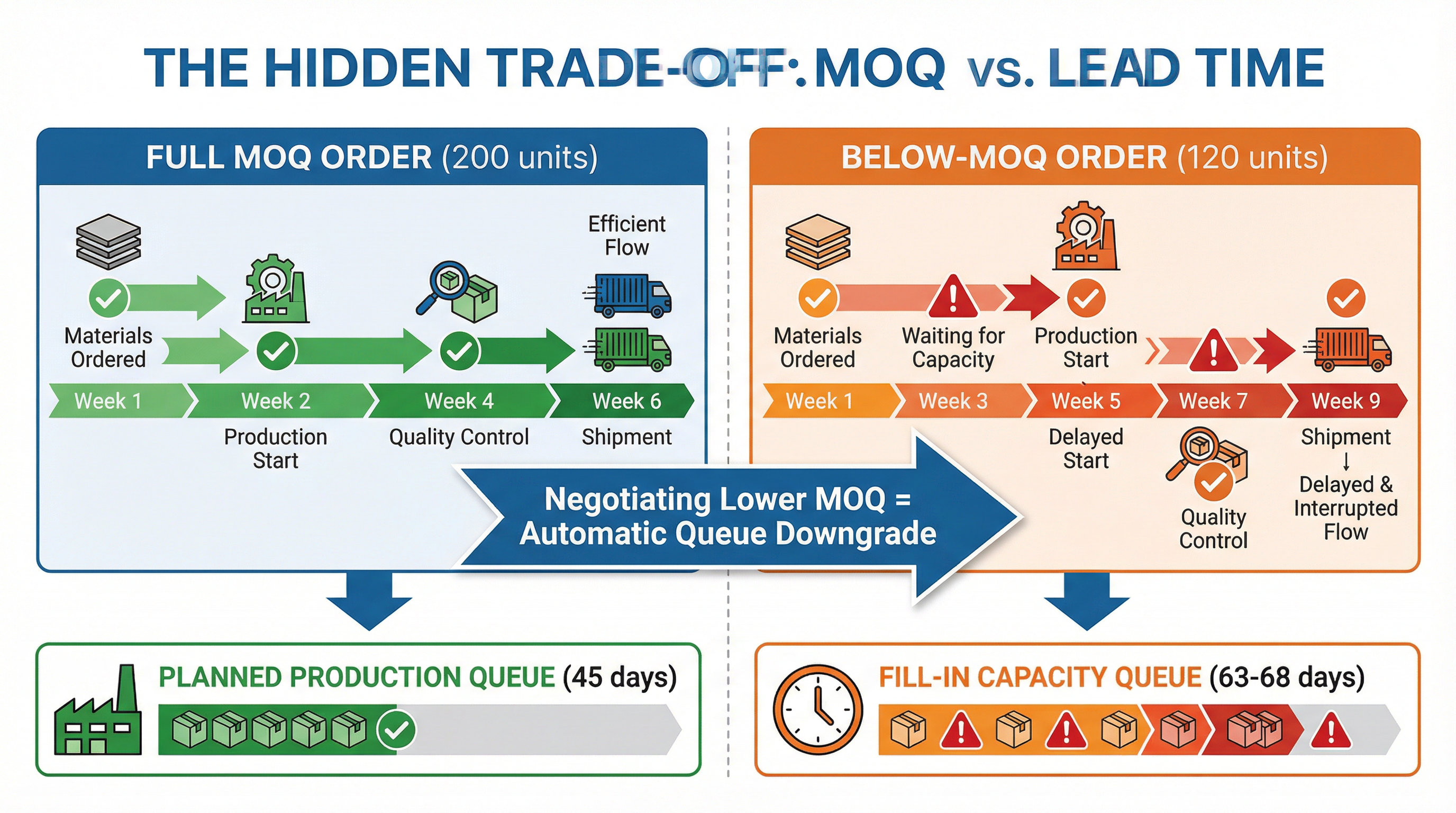

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks