You receive samples from a new corporate gift supplier. The leather notebooks look good. The pricing is competitive. You decide to place a 300-unit trial order to test quality before committing to your annual requirement of 1,200 units.

The trial order arrives. The quality is acceptable, but you notice some issues. The leather grain texture varies slightly between units. The embossing depth is inconsistent—some logos are crisp, others slightly shallow. The stitching tension differs across batches. Nothing is defective, but the consistency is not what you expected from a supplier claiming "premium quality standards."

You conclude that this supplier cannot meet your quality requirements. You move on to the next option.

What you did not realize is that those quality variations were not a reflection of the supplier's capability. They were artifacts of small batch production. At 1,000 units, those issues would largely disappear. You just rejected a capable supplier based on misleading quality data.

This is one of the most common misjudgments in corporate gift procurement. Buyers treat trial orders as accurate quality predictors. They are not. Small batch production operates under fundamentally different manufacturing conditions than volume production, and those conditions create quality characteristics that do not represent what you will receive at full minimum order quantity.

Why Small Batch Production Introduces Quality Variability

From a manufacturing perspective, producing 300 units versus 1,000 units is not simply a matter of running the same process for a shorter time. It changes how production is organized, how equipment is set up, and how quality control is executed.

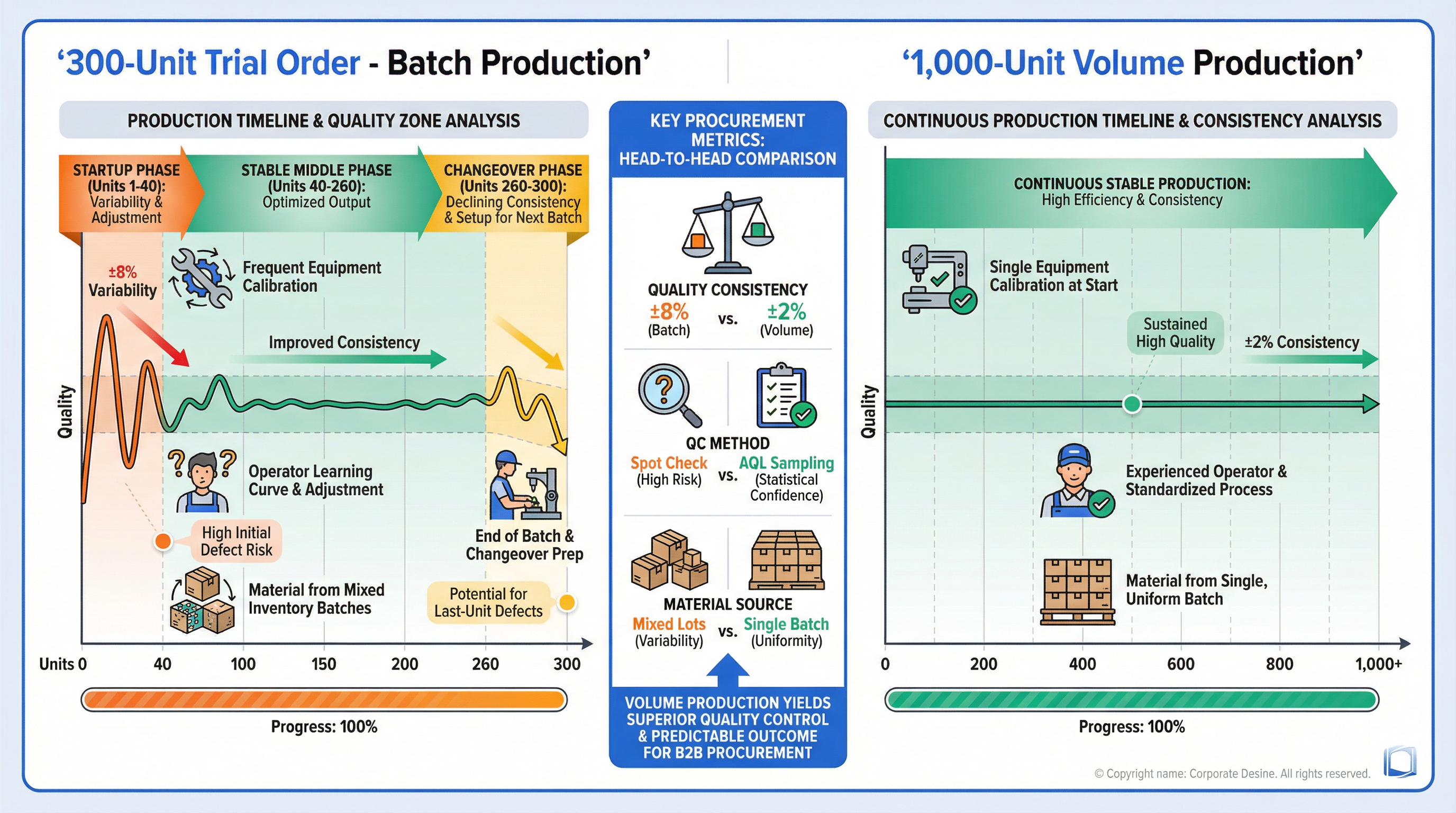

When a factory receives a 300-unit order, it typically processes this as a batch production run. The production line is set up specifically for your order, runs for a limited time, then is reconfigured for the next customer's order. This setup-run-changeover cycle introduces multiple points where variability enters the process.

Consider leather embossing for corporate notebooks. At volume production (1,000+ units), the embossing press runs continuously for several hours. The equipment reaches thermal equilibrium—the heating plates stabilize at a consistent temperature, the pressure remains constant, and the operator develops a rhythm. After the first 50-100 units, the process becomes highly stable. The embossing depth, clarity, and finish become remarkably consistent across the remaining 900+ units.

At 300 units, the process never reaches that stability point. The equipment is still warming up for the first 30-40 units. The operator is still adjusting pressure and dwell time. By the time the process stabilizes around unit 80-100, you are already one-third through the production run. Then, as the run nears completion, the factory begins preparing for changeover—cleaning embossing dies, adjusting for the next customer's specifications. The last 40-50 units are produced during this transition period.

The result is that your 300-unit trial order contains three distinct quality zones: startup units with slight variations as the process stabilizes, a middle section with good consistency, and end-run units affected by changeover preparation. When you inspect the delivered order, you see this variability and interpret it as the supplier's normal quality standard. It is not. It is the quality signature of batch production.

The Equipment Calibration Factor

Another source of quality variability in small batch production is equipment calibration frequency. Factories calibrate production equipment based on run length and production volume, not on individual orders.

For processes like pad printing, screen printing, or hot stamping on corporate gifts, equipment calibration affects registration accuracy, ink density, and finish consistency. At volume production, the factory calibrates equipment at the start of a long run, then maintains those settings throughout production. Any minor drift in calibration affects all units equally, so the output remains consistent relative to itself.

At small batch production, your 300-unit order might be the third or fourth job run on the same equipment setup that day. The screen printing press was calibrated this morning for a 2,000-unit drinkware order. Your 300-unit order runs in the afternoon using the same calibration, but the equipment has now been operating for six hours. Ink viscosity has changed slightly due to temperature. Screen tension has relaxed minimally. Registration has drifted by 0.3mm—imperceptible on the drinkware with bold graphics, but noticeable on your corporate stationery with fine text.

The factory does not recalibrate between every small batch order. The cost and time required make that impractical. Instead, they work within acceptable tolerance ranges that accommodate minor equipment drift. For volume orders, they recalibrate because the long run justifies the setup time. For your 300-unit trial, they use the existing calibration and work within broader tolerances.

When you receive your trial order and notice slight registration variations or ink density differences between units, you are seeing the effect of shared equipment calibration across multiple small batch jobs. At 1,000 units, your order would justify dedicated calibration, and those variations would largely disappear.

Material Consistency in Small Batch Orders

Material sourcing for small batch production introduces another layer of quality variability that buyers rarely consider. Factories do not purchase materials specifically for individual 300-unit orders. They draw from existing inventory, and that inventory may contain materials from multiple production lots with slight variations.

Consider leather for corporate gift notebooks. A tannery produces leather in large batches—typically 500-1,000 hides per production run. Each batch has slight variations in grain texture, color tone, and thickness due to differences in raw hide quality, tanning conditions, and finishing processes. These variations are normal and fall within industry tolerances.

When a factory receives an order for 1,000 leather notebooks, they purchase leather from a single tannery batch. All notebooks are cut from hides processed together, ensuring maximum consistency in grain texture and color tone. The factory can also negotiate specific requirements—"we need hides from the center selection with minimal grain variation"—because the order volume justifies that level of material specification.

When you place a 300-unit trial order, the factory pulls leather from existing inventory. That inventory likely contains remnants from two or three different tannery batches. The first 120 notebooks might be cut from batch A, the next 100 from batch B, and the final 80 from batch C. Each batch has slightly different grain characteristics. When you inspect the delivered order, you notice that some notebooks have a finer grain texture while others are slightly coarser. You interpret this as poor quality control. In reality, it is the material sourcing reality of small batch production.

The same pattern applies to metal components, textiles, and packaging materials. Volume orders justify purchasing materials from a single production lot with tight specifications. Small batch orders are fulfilled from mixed inventory, introducing material variations that would not exist at full minimum order quantity.

Quality Control Methodology Differences

Perhaps the most significant difference between small batch and volume production is how quality control is executed. The inspection protocols, sampling frequencies, and acceptance criteria change based on order volume, and these changes directly affect the quality consistency you observe.

For volume production orders, factories implement statistical process control based on international standards like AQL (Acceptable Quality Limit) sampling. A 1,000-unit order might be inspected using AQL Level II with a 2.5% acceptance threshold. The inspector examines approximately 80 units selected at random intervals throughout production. This sampling approach catches systematic quality issues—problems affecting multiple units due to equipment malfunction, material defects, or process errors.

For small batch orders like your 300-unit trial, factories typically use simpler inspection methods. They might inspect the first 10 units, then spot-check every 20th unit, and conduct a final inspection of 15-20 units before shipping. This approach catches obvious defects but is less effective at identifying subtle consistency issues across the entire batch.

The difference in inspection methodology means that small batch orders may contain more unit-to-unit variation that would be caught and corrected in volume production. When you receive your 300-unit trial and notice inconsistencies in stitching tension or surface finish, you might be seeing variations that would trigger a process adjustment in volume production but fell within the acceptable range for small batch inspection.

There is also a practical reality about quality control resource allocation. Factories assign their most experienced QC inspectors to large, high-value orders. Your 300-unit trial order, while important to you, represents perhaps 2-3% of the factory's daily output. It receives competent inspection, but not the intensive scrutiny that a 5,000-unit order commands. This difference in QC resource allocation affects the consistency of what you receive.

The Operator Experience Factor

Manufacturing quality is not solely determined by equipment and materials. Operator skill and experience play a significant role, particularly for processes requiring manual adjustment or judgment. The operators assigned to small batch versus volume production often have different experience levels, and this affects output consistency.

Volume production runs are typically assigned to the factory's most experienced operators. A 1,000-unit embossing job might run for two full days on a single press, and the factory assigns a senior operator who can maintain consistent quality throughout that extended run. This operator has years of experience reading leather response to heat and pressure, making micro-adjustments to maintain embossing clarity as conditions change throughout the day.

Small batch orders are often assigned to less experienced operators or are fit into production schedules as fill-in work between larger jobs. A junior operator might handle your 300-unit order as training, supervised by a senior operator who is simultaneously managing a larger production run. The junior operator follows the process specifications correctly, but lacks the intuitive adjustments that come with experience. The result is acceptable quality with more unit-to-unit variation than you would see from a senior operator on a volume run.

This is not a reflection of the factory's capability. It is a reflection of how factories allocate human resources based on order economics. Your 300-unit trial does not justify dedicating a senior operator for a full day. At 1,000 units, it would, and the quality consistency would improve accordingly.

When Trial Order Quality Is Actually Better Than Volume Production

Interestingly, the relationship between trial order quality and volume production quality is not always in the direction procurement teams expect. Sometimes, small batch trial orders show better quality than what you will receive at full minimum order quantity, creating a different type of misjudgment.

This occurs when factories treat trial orders as showcase opportunities. They know that trial orders often lead to larger commitments, so they apply extra attention and resources to ensure the trial succeeds. The production manager personally oversees setup. The most experienced operators are assigned. Materials are hand-selected from the best available inventory. Quality inspection is more thorough than normal.

The 300-unit trial order you receive represents the factory's best-case quality—what they can achieve when applying maximum attention and resources. When you subsequently place a 1,000-unit order based on that trial quality, you receive good quality, but not quite the same level of perfection. The factory is now treating your order as routine production, not as a showcase opportunity.

This creates a procurement disappointment. You approved the supplier based on trial quality, expecting that same level in volume production. The volume order meets specifications and is objectively good quality, but it does not match the trial. You feel misled, even though the factory did nothing wrong. They simply applied normal production practices instead of showcase practices.

The misjudgment here is assuming that trial order quality represents normal production capability. It often represents best-case capability under ideal conditions. Understanding this distinction helps set realistic quality expectations when scaling from trial to volume orders.

How This Affects Supplier Selection Decisions

The quality variability inherent in small batch production creates systematic errors in supplier evaluation. Procurement teams use trial orders to compare suppliers, not realizing that they are comparing batch production artifacts rather than actual manufacturing capability.

You request 300-unit trial orders from three suppliers for the same corporate gift notebook. Supplier A delivers with noticeable leather grain variation. Supplier B shows slight embossing depth inconsistency. Supplier C has perfect consistency across all 300 units. Based on this trial, you select Supplier C.

What you did not consider is that Supplier C might have treated your trial as a showcase order, applying extra resources and attention that they will not maintain at volume production. Supplier A and B delivered using their normal production processes, showing you realistic quality for volume orders. When you place your 1,000-unit order with Supplier C, you might be disappointed. When you rejected Suppliers A and B, you might have eliminated factories that would have delivered better consistency at volume.

The solution is not to avoid trial orders. They serve valuable purposes—verifying that the supplier can meet basic specifications, assessing communication and responsiveness, confirming that samples match production. The solution is to interpret trial order quality correctly, understanding that small batch production introduces variability that may not represent volume production capability.

When evaluating trial orders, focus on whether the supplier meets specifications rather than on unit-to-unit consistency. Slight variations in surface finish, color tone, or dimensional tolerances are normal in batch production and often disappear at volume. Systematic defects—incorrect dimensions, wrong materials, process failures—are legitimate concerns regardless of order size.

For a more accurate assessment of volume production quality, consider requesting a factory visit to observe a volume production run for another customer, or ask for quality data from previous volume orders of similar products. These provide better insight into what you can expect at full minimum order quantity than a 300-unit trial order can offer.

The Cost of Misjudging Trial Order Quality

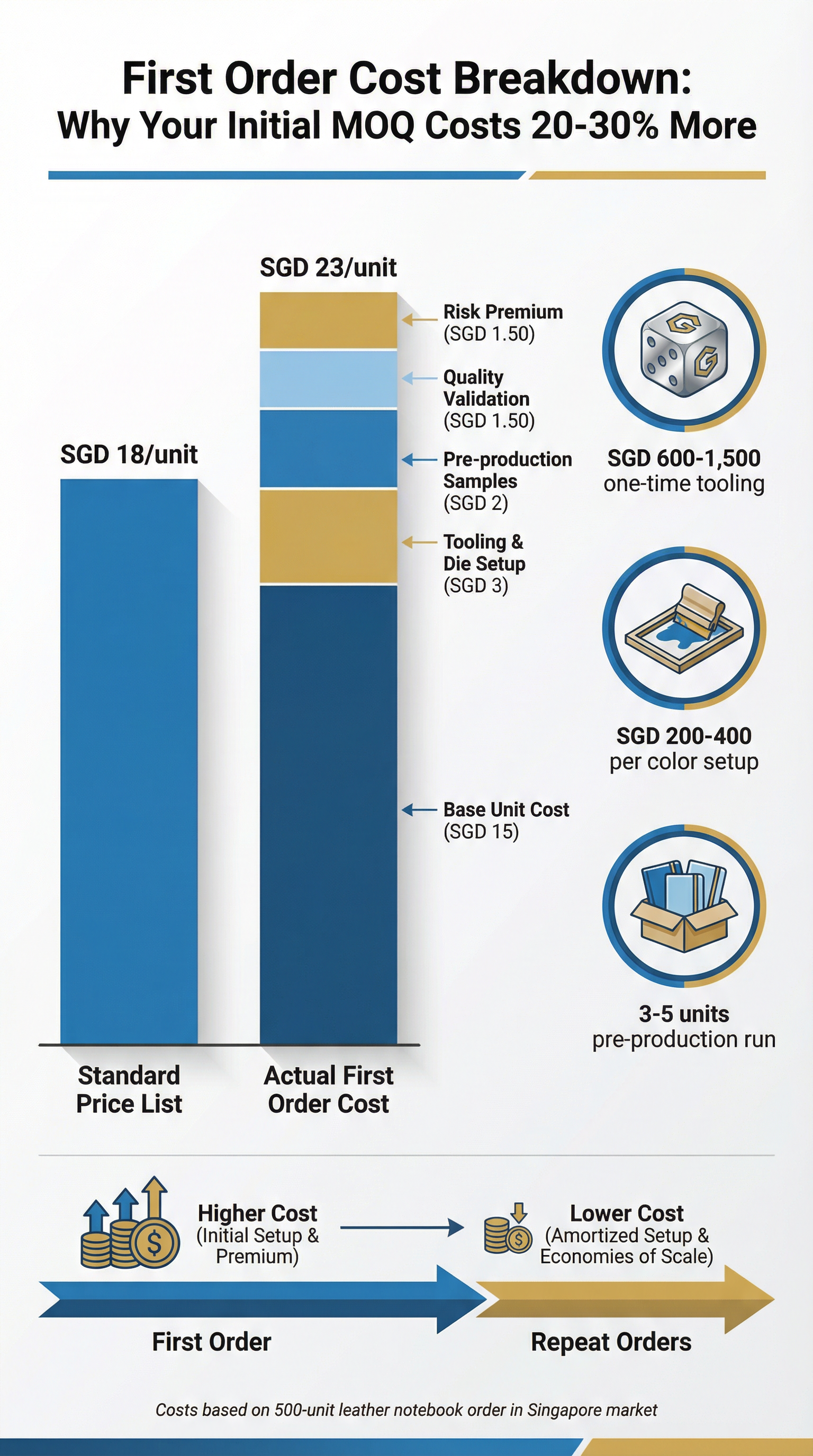

The procurement cost of misinterpreting trial order quality extends beyond selecting the wrong supplier. It affects pricing negotiations, quality specification development, and long-term supplier relationship dynamics.

When you reject a capable supplier based on trial order quality issues that would not exist at volume, you eliminate a potential long-term partner and must restart the supplier search process. This extends your procurement timeline by 4-8 weeks and increases the risk of missing your delivery deadline. The cost of that delay—rush shipping fees, lost sales opportunities, or event cancellations—can far exceed any quality concerns from the trial order.

When you approve a supplier based on showcase trial quality that does not represent their normal production, you create unrealistic quality expectations that lead to disputes when volume orders arrive. These disputes damage the supplier relationship, consume management time in negotiations, and may require costly rework or replacements. In some cases, the relationship deteriorates to the point where you must find a new supplier mid-season, creating supply chain disruption.

The misjudgment also affects how you write quality specifications. If you base specifications on trial order quality without understanding batch production variability, you may set tolerances that are unnecessarily tight for volume production. This increases manufacturing costs, extends lead times, and reduces the number of suppliers who can meet your requirements. You have essentially specified for batch production quality when you actually need volume production quality.

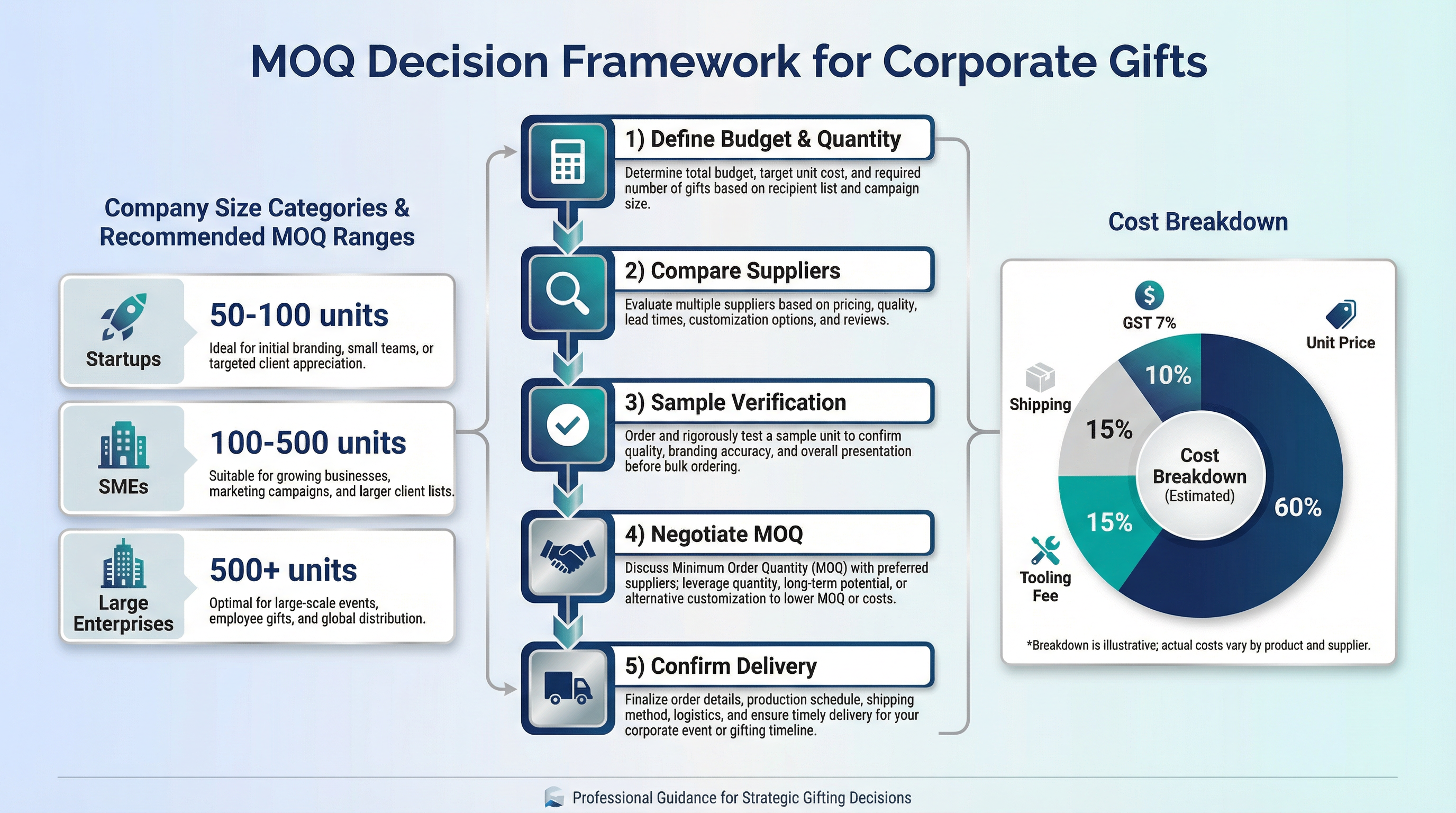

Understanding how trial order quality relates to volume production quality allows you to make more informed supplier selection decisions, set realistic quality expectations, and develop specifications that balance quality requirements with manufacturing economics. For a comprehensive understanding of how minimum order quantities affect overall procurement decisions, including supplier capability assessment and quality planning, see our complete guide on minimum order quantities for corporate gifts in Singapore.

The relationship between order volume and quality consistency is one of the least understood aspects of corporate gift procurement. Small batch trial orders serve important purposes, but quality assessment is not their primary value. They verify basic capability and establish communication, but they do not accurately predict volume production quality. Recognizing this limitation prevents costly supplier selection errors and sets the foundation for successful long-term sourcing relationships.

Related Articles

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

What Is the Minimum Order Quantity for Corporate Gifts in Singapore?

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

Why Your First Corporate Gift Order Costs More Than the Quote Suggested

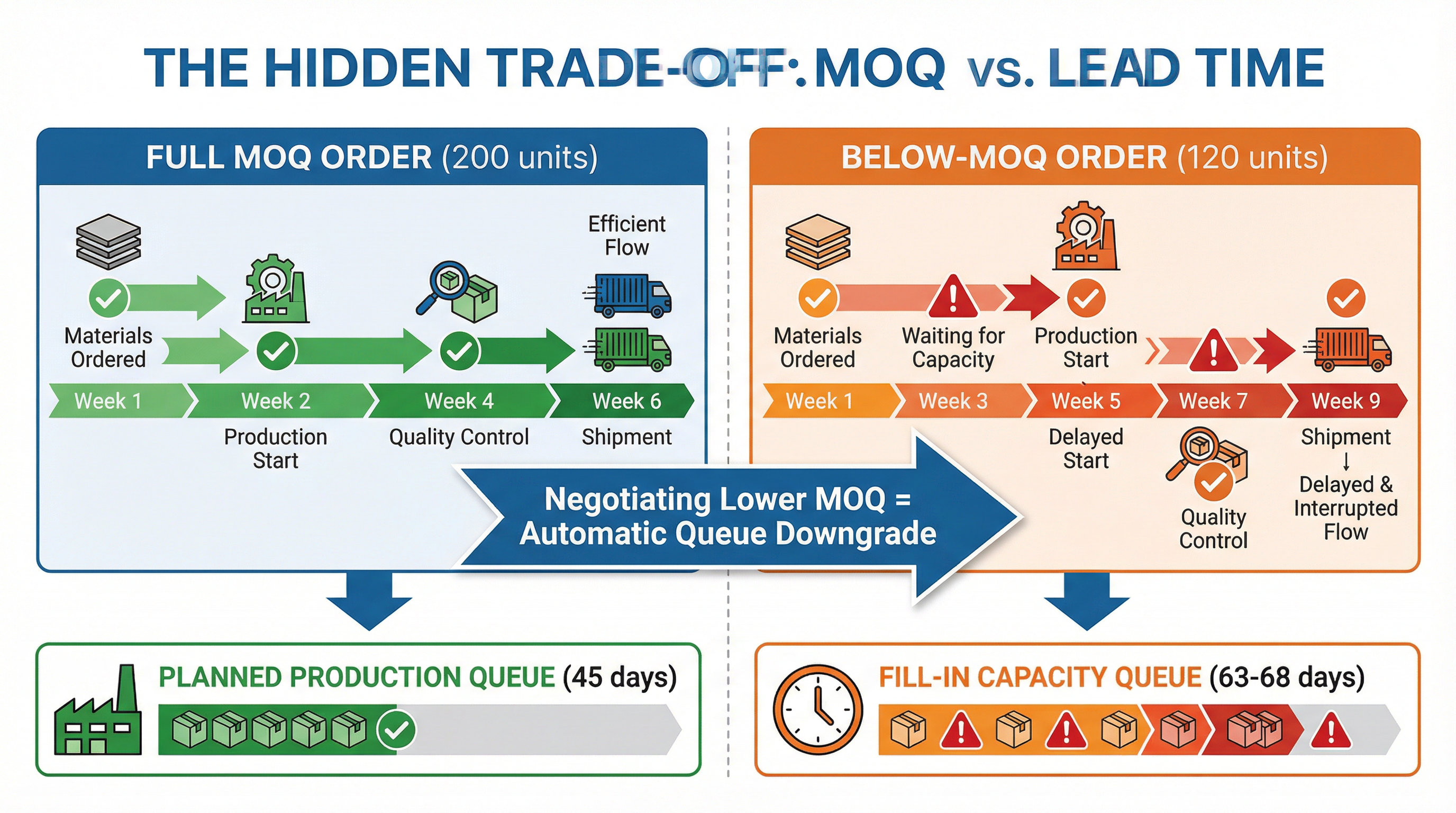

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks

When Negotiating Lower MOQ Actually Extends Your Delivery Date by Six Weeks