UV Printing Ink Curing: Wavelength Optimization for Multi-Material Corporate Gift Decoration

When a promotional product supplier quotes a 48-hour turnaround for 5,000 custom-printed power banks, the unspoken technical backbone of that promise is UV curing technology. Unlike conventional solvent-based or water-based inks that require minutes or hours to dry through evaporation, UV inks cure in seconds under ultraviolet light exposure. This speed advantage has made UV printing the dominant decoration method for corporate gifts—but achieving consistent, durable results across different substrate materials demands precise control over curing wavelength, intensity, and exposure time.

Working alongside equipment engineers in Southeast Asian manufacturing facilities, I've observed how seemingly minor variations in UV lamp specifications can cascade into visible quality differences: incomplete cure leading to ink smudging during packaging, over-cure causing surface brittleness and cracking, or wavelength mismatch resulting in poor adhesion that fails tape tests. The technical challenge isn't simply "turning on the UV lamp"—it's matching the photoinitiator chemistry in the ink formulation to the spectral output of the lamp, while accounting for how different substrate materials absorb or reflect UV energy.

The Chemistry Behind Instant Cure: Photoinitiators and Radical Polymerization

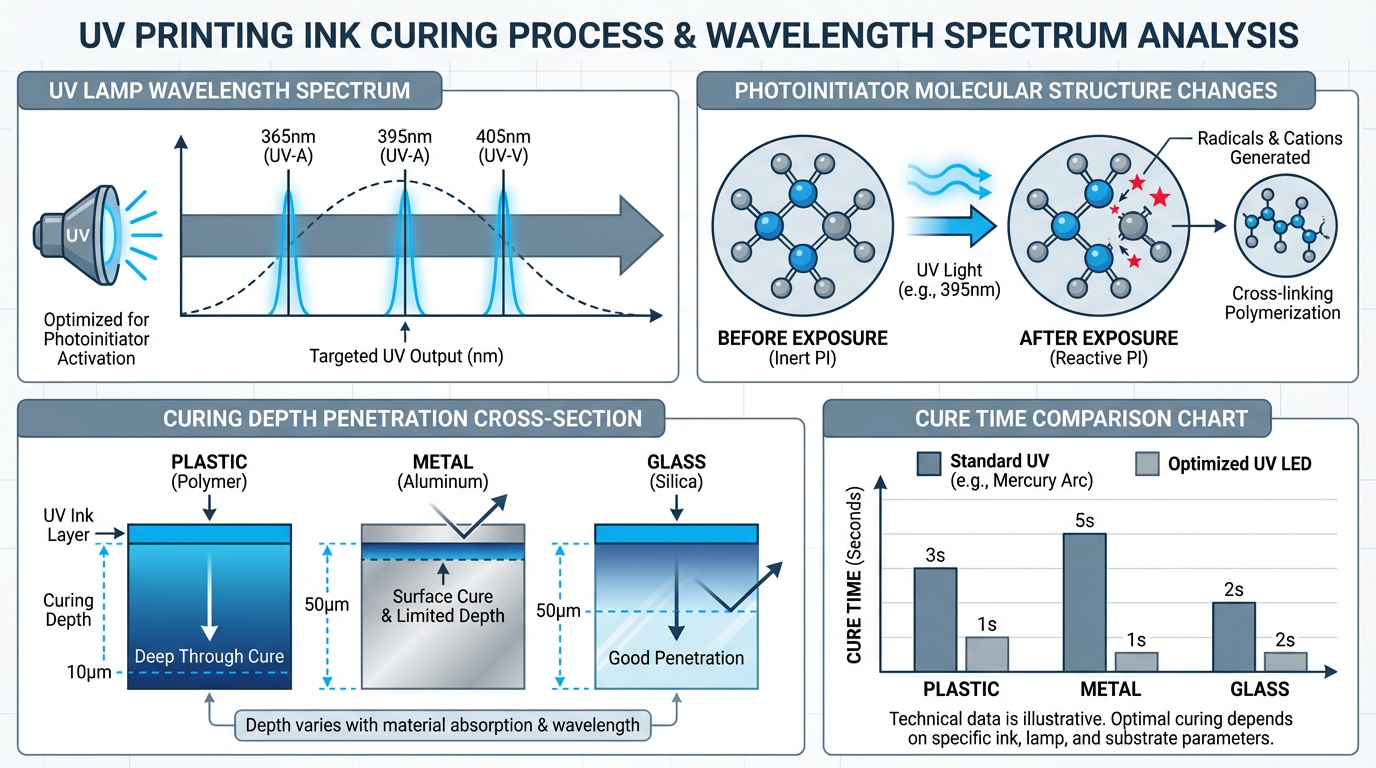

UV ink doesn't "dry" in the conventional sense—it undergoes a photochemical reaction called radical polymerization. The ink formulation contains three key components: pigments for color, oligomers and monomers that form the polymer matrix, and photoinitiators (PI) that trigger the curing reaction. When UV photons strike the photoinitiator molecules, they absorb the energy and split into highly reactive free radicals. These radicals initiate a chain reaction that cross-links the monomers and oligomers into a solid polymer film within 0.5 to 2 seconds of exposure.

The critical variable here is the absorption spectrum of the photoinitiator. Different PI chemistries absorb UV energy most efficiently at specific wavelengths. The most common photoinitiators used in commercial UV inks are designed to absorb in the UV-A range (315-400nm), with peak absorption typically around 365nm or 395nm. However, newer LED-based UV systems often emit at 385nm or 405nm, which requires ink formulations with photoinitiators optimized for those wavelengths. A mismatch between lamp output and PI absorption spectrum results in incomplete cure—the surface may feel dry, but the ink layer beneath remains under-polymerized, leading to poor scratch resistance and adhesion failure.

Lamp Technology: Mercury Arc vs. LED UV Systems

Traditional UV curing systems use mercury arc lamps, which emit a broad spectrum of UV radiation from 200nm to 400nm, with strong peaks at 365nm and 405nm. These lamps generate significant heat (often requiring active cooling systems) and have a lifespan of 1,000 to 2,000 hours before output intensity degrades. The broad-spectrum output means they can cure a wide range of ink formulations, but the heat generation can be problematic for heat-sensitive substrates like thin plastics or pre-assembled electronics.

LED UV systems, which have gained dominance in the past decade, emit a narrow-band spectrum centered at a specific wavelength—typically 365nm, 385nm, 395nm, or 405nm. The advantages are substantial: instant on/off (no warm-up time), lower heat generation, longer lifespan (20,000+ hours), and lower energy consumption. However, the narrow spectral output demands precise matching with the ink's photoinitiator. An ink formulated for 365nm mercury lamps may cure poorly under a 395nm LED system, even though both are technically "UV-A" wavelengths.

In practical terms, this means a manufacturer switching from mercury to LED UV systems cannot simply swap the lamps—they must also reformulate or source inks specifically designed for the LED wavelength. I've seen production lines experience a 30-40% increase in defect rates during this transition period, primarily due to incomplete cure or adhesion failures, until the ink chemistry was properly matched to the new lamp spectrum.

Substrate-Specific Challenges: How Materials Affect Cure Depth and Adhesion

The substrate material introduces another layer of complexity. UV energy doesn't just interact with the ink—it also interacts with the substrate surface, and different materials absorb, reflect, or transmit UV light in different ways. This affects both cure depth (how deeply the UV penetrates the ink layer) and adhesion (how well the cured ink bonds to the substrate).

Plastic (Polycarbonate, ABS, Polypropylene): Most plastics are relatively transparent to UV-A wavelengths, allowing good penetration and deep cure. The challenge with plastics is surface energy—many plastics have low surface energy (around 30-35 dynes/cm), which makes it difficult for the liquid ink to wet the surface and for the cured polymer to form strong chemical bonds. Pre-treatment with corona discharge or flame treatment is often necessary to raise the surface energy above 40 dynes/cm before printing. Without this step, the ink may cure perfectly but peel off with minimal force.

Metal (Aluminum, Stainless Steel): Metal surfaces reflect a significant portion of UV light, particularly at shorter wavelengths. This reflection can actually be beneficial—the reflected UV contributes to curing the ink from below, resulting in faster and more complete polymerization. However, the smooth, non-porous nature of metal means adhesion relies entirely on mechanical interlocking (surface roughness) and chemical bonding. Anodized aluminum provides better adhesion than bare aluminum due to its micro-porous oxide layer. For stainless steel, a primer layer is often required to achieve acceptable adhesion.

Glass (Borosilicate, Soda-Lime): Glass is highly transparent to UV-A wavelengths, which creates a unique challenge: the UV light passes through the ink layer and the glass substrate, then reflects back from any surface behind the glass. This can lead to over-cure if the exposure time isn't carefully controlled. Over-cured UV ink on glass becomes brittle and prone to micro-cracking, especially if the printed item undergoes thermal cycling (e.g., a glass tumbler going from refrigerator to dishwasher). The optimal cure for glass typically requires 30-50% less exposure time than plastic or metal.

Optimizing Cure Parameters: Balancing Speed, Adhesion, and Durability

The equipment engineer's task is to find the optimal combination of lamp power (measured in watts/cm), conveyor speed (meters/minute), and lamp-to-substrate distance that achieves complete cure without over-curing or heat damage. This optimization process typically involves iterative testing with a spectrophotometer to measure cure depth and a cross-hatch adhesion test to verify bond strength.

For a typical UV LED system operating at 395nm with 10 W/cm output, the baseline parameters for different substrates might look like this:

| Substrate | Conveyor Speed | Lamp Distance | Cure Time | Surface Temp |

|-----------|----------------|---------------|-----------|--------------|

| ABS Plastic | 15 m/min | 8mm | 0.8s | 45°C |

| Anodized Aluminum | 12 m/min | 8mm | 1.0s | 55°C |

| Soda-Lime Glass | 20 m/min | 10mm | 0.6s | 40°C |

These are starting points, not universal standards—actual optimal parameters depend on ink formulation, substrate surface treatment, and print layer thickness. A thicker ink layer (e.g., white base coat) requires longer exposure than a thin color layer. Multi-layer prints (white base + color + clear coat) require multiple curing passes, each optimized for the specific layer.

One common mistake is assuming "more UV is always better." Over-curing causes the polymer network to become overly cross-linked and brittle, reducing flexibility and impact resistance. For items that will experience handling or flexing (like phone cases or wristbands), a slightly under-cured ink with retained flexibility often performs better in real-world use than a fully maximized cure that passes lab tests but cracks in the field.

Troubleshooting Common UV Curing Defects

Incomplete Cure (Tacky Surface): Most often caused by wavelength mismatch between lamp and photoinitiator, insufficient UV intensity, or contamination of the ink with oxygen (which inhibits radical polymerization). Solution: Verify lamp wavelength matches ink specification, increase exposure time or lamp power, or implement nitrogen inerting to displace oxygen during cure.

Poor Adhesion (Ink Peeling): Typically a substrate surface energy issue rather than a curing problem. Solution: Implement corona or flame pre-treatment to raise surface energy, or switch to an ink formulation with adhesion promoters designed for the specific substrate chemistry.

Color Shift or Yellowing: Can occur with over-cure, particularly with white inks that contain titanium dioxide pigments. Excessive UV exposure causes photo-oxidation of the polymer binder. Solution: Reduce exposure time, lower lamp intensity, or switch to a UV-stabilized ink formulation.

Cracking or Brittleness: Sign of over-cure or incompatible ink chemistry for flexible substrates. Solution: Reduce cure energy, switch to a flexible UV ink formulation with lower cross-link density, or implement a post-cure annealing step to relieve internal stress.

The Future: UV-C and Dual-Cure Systems

Emerging technologies are pushing UV curing into new territory. UV-C wavelengths (200-280nm) offer even faster cure times and can activate photoinitiators that are completely insensitive to visible light, eliminating issues with premature curing during handling. However, UV-C systems require specialized safety protocols due to the germicidal properties of these wavelengths.

Dual-cure systems, which combine UV initiation with thermal post-cure, are gaining traction for applications requiring exceptional chemical resistance or high-temperature performance. The UV exposure provides rapid initial cure for handling, while a subsequent thermal bake (typically 80-120°C for 10-30 minutes) completes the polymerization and enhances cross-link density. This approach is particularly valuable for premium drinkware or items that will undergo repeated washing cycles.

For procurement teams evaluating suppliers, the key technical questions aren't just "Do you use UV printing?" but rather "What wavelength are your UV systems, how do you match ink formulations to your lamps, and what surface pre-treatment protocols do you implement for different substrate materials?" The answers to these questions reveal whether a supplier truly understands the photochemistry behind their decoration process—or is simply running items under a UV lamp and hoping for the best.

When you receive a quote for UV-printed corporate gifts, you're not just paying for ink and labor—you're paying for the accumulated knowledge of how to make photons, photoinitiators, and polymer chemistry work in harmony across materials that were never designed to be printed on. That's the invisible technical foundation that makes your 48-hour turnaround possible.

Related Articles

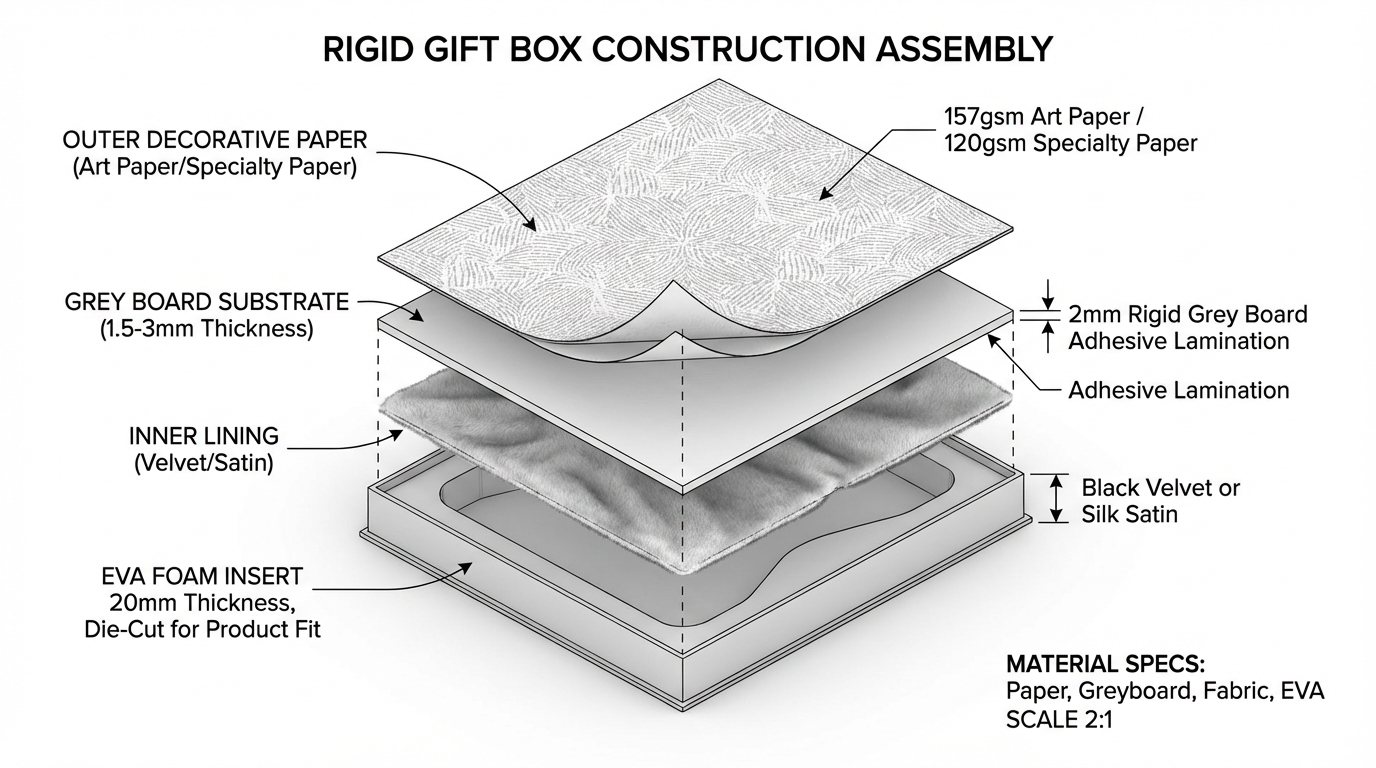

Understanding Rigid Gift Box Construction: A Material Layer Analysis for Corporate Packaging

A technical breakdown of rigid gift box construction layers, from grey board substrate to EVA foam inserts, with material specifications and assembly considerations for premium corporate packaging.

Leather Embossing Temperature Control: Why 10°C Makes the Difference Between Sharp Logos and Burnt Leather

Technical analysis of heat press temperature control in leather embossing for corporate gifts, covering brass die specifications, leather grain response, and pressure calibration for consistent branding results.

EVA Foam Insert Precision: How ±0.5mm Tolerances Affect Corporate Gift Presentation

Technical examination of die-cutting tolerances for EVA foam inserts in corporate gift packaging, covering foam density selection, cutting methods, and cavity design for secure product positioning.