Most procurement teams calculate their booking window by working backward from the delivery deadline. If the corporate event is scheduled for mid-December and the supplier quotes an eight-week production lead time, the internal calendar shows an October order placement as "comfortably early." The math appears sound: eight weeks of production plus two weeks of buffer equals ten weeks total, leaving the team with what feels like adequate margin.

From the factory floor, this calculation misses the fundamental mechanism that determines whether a buyer secures optimal production conditions or gets pushed into a compromised position. Suppliers do not allocate peak season capacity by counting backward from delivery dates. They allocate it by counting forward from the current date, filling production slots in the order that confirmed commitments arrive. By the time a procurement team places that "early" October order for December delivery, the production window they are targeting has often been claimed by buyers who made their commitments in July or August.

This timing mismatch creates a systematic pattern where procurement teams believe they are booking early when, from the supplier's operational perspective, they are booking late. The consequences extend far beyond simple availability. Late positioning in the production queue triggers a cascade of penalties: reduced material selection, compressed quality control windows, higher per-unit costs, and diminished negotiation leverage. Understanding why this disconnect occurs requires examining how production capacity allocation actually functions during peak demand periods.

Peak season capacity does not become "unavailable" at a single point in time. It erodes gradually as suppliers receive inquiries, issue quotes, and convert those quotes into confirmed purchase orders. For corporate gift box production targeting Q4 delivery or Chinese New Year distribution, this erosion process typically begins three to four months before the actual production window opens. Major corporate clients with multi-year relationships often secure their preferred production slots through early-stage discussions that never appear in formal RFQ processes. These conversations happen in June and July for December deliveries, or in September and October for February Chinese New Year orders.

When a procurement team initiates their vendor selection process in September for December delivery, they are entering a market where the most favorable production slots have already been mentally allocated, even if formal purchase orders have not yet been signed. Suppliers maintain running tallies of anticipated demand based on historical patterns, ongoing client relationships, and early-stage inquiries. A factory project manager reviewing production capacity in mid-September already has a mental picture of how November and December production lines will be utilized, based on commitments and near-commitments that accumulated over the previous two months.

The procurement team working from an eight-week lead time calculation does not see this invisible allocation. They see a supplier who confirms availability and quotes standard pricing. What they do not see is that their order is being slotted into a secondary tier of the production queue, behind the orders that arrived when capacity was abundant and suppliers could offer optimal terms. This secondary positioning becomes visible only when production begins and the team discovers that their customization requests face more restrictions, their quality control checkpoints are more compressed, or their delivery buffer has been reduced to accommodate higher-priority orders that claimed earlier queue positions.

The cost structure of late booking reflects this queue positioning rather than simple supply and demand dynamics. When suppliers quote premium pricing for orders that arrive in October for December delivery, the premium is not merely a response to high demand. It is compensation for the operational disruption of inserting a new order into a production schedule that is already substantially planned. Accommodating a late order requires the factory to either compress existing production timelines, extend working hours, or deprioritize other commitments. Each of these adjustments carries real costs that get passed to the buyer through premium pricing, rushed production fees, or reduced flexibility in material selection and customization options.

Material availability illustrates this queue priority mechanism clearly. Corporate gift box production relies on specialized packaging materials, custom printing plates, and branded components that require their own lead times. When a buyer commits to an order in July for December delivery, the supplier can source optimal materials through standard procurement channels, negotiate favorable terms with material vendors, and maintain quality standards without time pressure. When a buyer commits in October for the same December delivery window, the supplier must source materials through expedited channels, accept whatever inventory is available from material vendors, and compress quality verification processes to meet the delivery deadline.

The procurement team sees this material constraint as a limitation of their specific supplier, not recognizing that it is a systemic consequence of their late queue position. They may attempt to solve the problem by switching suppliers, only to discover that alternative vendors face identical constraints because the entire supply chain operates on the same forward-looking capacity allocation model. The window for securing optimal material selection closed weeks before the procurement team initiated their vendor selection process.

Quality control windows follow the same pattern. When production schedules are built with adequate buffer time, quality control can function as a genuine verification process with time to address any issues that emerge. When production schedules are compressed to accommodate late orders, quality control becomes a pass-fail checkpoint with limited capacity to implement corrections. The factory project manager knows that a December delivery order confirmed in July allows for a three-day quality control window with time to remake any units that fail inspection. The same December delivery order confirmed in October allows for a one-day quality control window where failed units must either ship as-is or cause the entire order to miss its delivery deadline.

This quality control compression does not appear in the supplier's quote or the production timeline shared with the buyer. It exists as an operational reality that becomes visible only when an issue emerges during production. The procurement team that booked in October discovers that their supplier is less willing to remake units or adjust specifications compared to the flexibility they expected based on initial discussions. This reduced flexibility is not a change in supplier attitude. It is a direct consequence of the compressed timeline that results from late queue positioning.

Negotiation leverage erodes in parallel with queue position. When a supplier receives an inquiry in July for December delivery, they are evaluating whether to accept the order against a backdrop of uncertain demand. They do not yet know how many orders will materialize for their peak season capacity, which creates incentive to offer competitive pricing and flexible terms to secure early commitments. When the same supplier receives an inquiry in October for December delivery, they are evaluating whether to accept the order against a backdrop of substantially committed capacity. They know their production lines are largely allocated, which eliminates the incentive to compete on price or terms.

The procurement team negotiating in October faces a supplier who can credibly walk away from the deal because alternative orders are available to fill any capacity that gets freed up. The procurement team negotiating in July faces a supplier who cannot credibly walk away because alternative orders are not yet certain. This shift in negotiation dynamics is invisible to buyers who focus solely on the quoted lead time rather than the broader context of capacity allocation timing.

For corporate gift box production timelines, the practical implication is that procurement teams need to shift their booking window calculation from delivery-date-backward to capacity-allocation-forward. Instead of asking "when do we need to order to receive delivery by our deadline," the question should be "when does our supplier begin allocating capacity for our target delivery window, and how early do we need to commit to secure optimal queue position."

For Q4 corporate gifting targeting November or December delivery, optimal queue positioning typically requires commitment by late July or early August, even though actual production may not begin until October. For Chinese New Year corporate gifting in Singapore targeting late January or early February delivery, optimal queue positioning typically requires commitment by mid-October, even though actual production may not begin until December. These timelines feel counterintuitively early because they are measured against capacity allocation cycles rather than production lead times.

The eight-week production lead time that suppliers quote is accurate as a measure of how long physical production requires. It is misleading as a measure of how far in advance buyers need to commit to secure favorable production conditions. The gap between these two timelines represents the invisible window where capacity is technically available but operationally allocated. Procurement teams that book during this invisible window receive confirmation of availability but sacrifice the cost advantages, material selection, quality control buffer, and negotiation leverage that come with early queue positioning.

Supplier communication practices reinforce this timing mismatch because factories rarely explicitly state that capacity is "filling up" until it is nearly exhausted. A supplier contacted in September about December delivery will confirm availability because capacity technically remains. They will not volunteer that optimal queue positions were claimed in July, or that the October production slots being offered come with implicit constraints that early bookers avoided. This information asymmetry exists not because suppliers are deliberately obscuring the situation, but because the gradual nature of capacity allocation makes it difficult to identify a clear threshold where "early" becomes "late."

From the factory project manager's perspective, the transition from early to late booking is not a discrete event but a continuous degradation. Each new order that arrives shifts existing orders slightly in terms of priority, flexibility, and resource allocation. The supplier cannot point to a specific date and declare "orders after this point are late" because the impact of booking timing accumulates gradually rather than manifesting as a binary availability threshold.

This gradual accumulation makes it difficult for procurement teams to learn from experience. A team that books in September for December delivery and receives their order on time may conclude that their timing was adequate, not recognizing that they paid premium pricing, accepted limited material options, and received compressed quality control compared to what they would have experienced with July booking. The successful delivery obscures the hidden costs of late queue positioning.

The seasonal nature of corporate gifting demand amplifies this timing challenge because procurement teams cannot rely on continuous relationship management to maintain queue priority. A procurement manager handling corporate gift boxes for a single annual event does not have the ongoing supplier interaction that would naturally surface capacity allocation patterns. They engage with suppliers once per year, which means they must rebuild their understanding of optimal booking timing with each cycle rather than developing intuition through frequent interaction.

Breaking this pattern requires procurement teams to explicitly map supplier capacity allocation cycles rather than relying on quoted lead times as booking guides. This mapping process involves asking suppliers not "what is your production lead time" but "when do you begin receiving commitments for [target delivery month] and when does your queue typically fill to the point where late orders face constraints." Most suppliers can answer this question accurately because they track these patterns internally for production planning purposes. They simply do not volunteer the information unless specifically asked.

For organizations managing corporate gifting across multiple regions or multiple annual events, documenting these capacity allocation cycles creates institutional knowledge that prevents the timing mismatch from recurring. A procurement team that learns through experience that their Singapore-based supplier begins allocating Chinese New Year capacity in September can encode that knowledge into their annual planning calendar, ensuring that future cycles initiate vendor selection early enough to capture optimal queue positions.

The cost of this timing mismatch is not catastrophic in the sense of causing project failure. Orders placed in October for December delivery generally do arrive on time, and the resulting gift boxes generally meet acceptable quality standards. The cost manifests as a systematic erosion of value: paying 15-20% more than necessary, accepting material substitutions that reduce perceived quality, and operating with delivery buffers that leave no room for addressing issues that emerge during production. These costs accumulate across procurement cycles without triggering the kind of visible failure that would force a systematic reevaluation of booking timing practices.

Understanding that suppliers allocate capacity forward from the current date rather than backward from delivery deadlines transforms how procurement teams should structure their planning calendars. The relevant timeline is not "how long does production take" but "when does the competition for favorable queue positions begin." For peak season corporate gift box orders, that competition begins three to four months before production starts, which means it begins four to five months before delivery occurs. Procurement teams that align their booking decisions with this capacity allocation reality secure the cost advantages, material selection, quality control buffer, and negotiation leverage that come with early queue positioning.

Related Articles

Approval Process Delays Eroding Production Lead Time for Corporate Gift Boxes

Approval Process Delays Eroding Production Lead Time for Corporate Gift Boxes

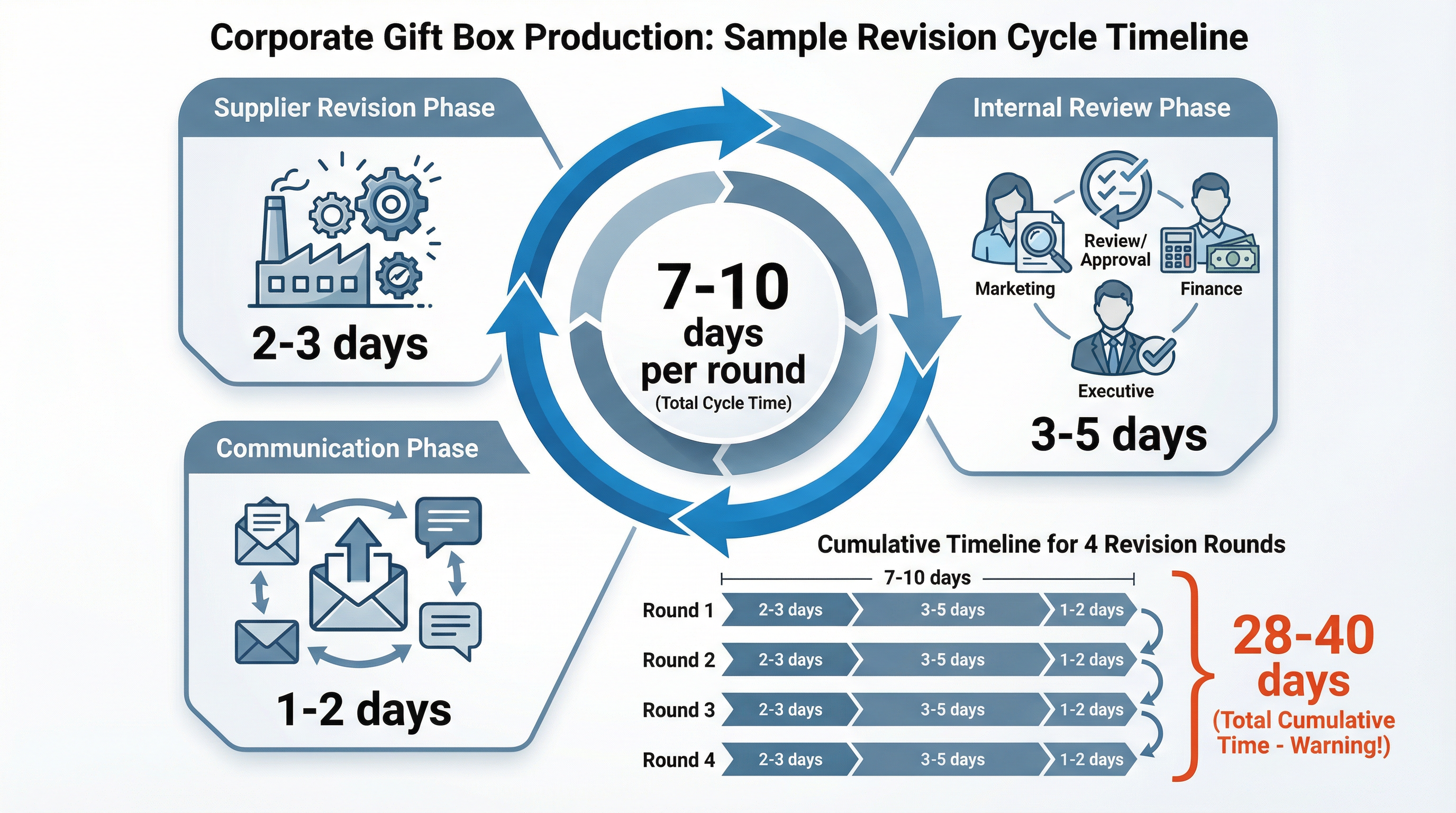

Sample Revision Iteration Creep in Corporate Gift Box Production

Procurement teams treat each sample revision as an isolated 2-3 day delay without realizing the fixed 7-10 day cycle time per round. Four rounds consume 28-40 days before production even starts, compressing quality control windows and pushing orders into lower-priority production queues.

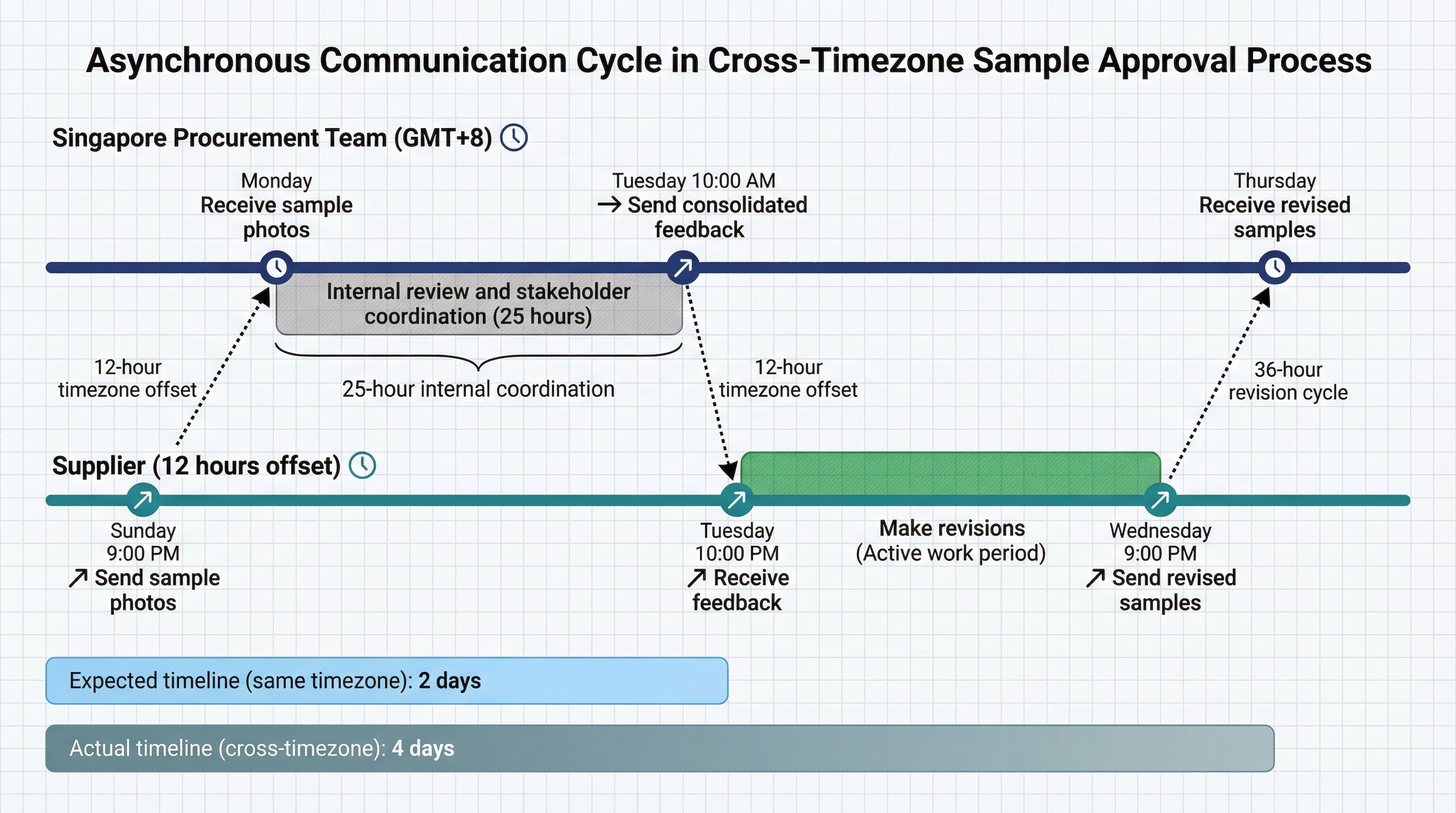

Cross-Timezone Asynchronous Approval Cycles in Corporate Gift Box Production

Cross-Timezone Asynchronous Approval Cycles in Corporate Gift Box Production